Railroads, Race, and the Transformation of Oregon

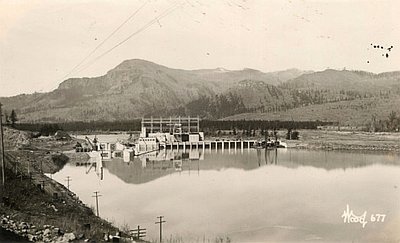

As symbols of the Industrial Revolution, railroads were powerful centralizing and dispersing mediums, concentrating populations in urban areas while also scattering people and communities across Oregon. Railroads also represented outside capital, with distant investors buying up mineral rights, timberland, and town lots and investing in new rail lines. Perhaps most importantly, however, railroads made raw materials more accessible to investors.

Even when railroads did not bring economic benefits to communities directly, the mere idea of their potential spurred business activity and excited the imaginations of developers, dreamers, and boosters. In both a physical and a psychological sense, railroads helped alleviate regional isolation, freeing passengers and freight from the constraints of geography and shortening both time and space with buyers and sellers in the Midwest and California. Railroad construction also challenged engineers, who found ways to tunnel through mountains and to build bridges and trestles across deep ravines.

In 1880, Portland was the region’s metropolitan center, with a population of 17,500, while Seattle had only 3,500 residents. During the next decade, however, transcontinental railroads began to reverse those urban dynamics. Although Portland’s population more than doubled to 46,385 by 1890, Seattle burgeoned to 42,837 during the same period and by 1900 had 90,426 compared to Portland’s 80,871.

Despite Seattle’s growth spurt, Portland remained the leading metropolis in the Northwest, a position it enjoyed at least through World War I. Ray Stannard Baker, a journalist who visited Portland in 1903, liked what he saw: “not a crude western town; Portland really is a fine old city, a bit, as it might be, of central New York—a square with a post office in the center, tree-shaded streets, comfortable homes and plenty of churches and clubs, the signs of conservatism and respectability.” Portland also continued to be a major power broker in Oregon politics, and the influence of its banks extended to the interior Columbia Basin and beyond the Willamette Valley to the south.

The completion of a northern transcontinental railroad brought new people, new ideas, and new groups to the Northwest. Even before the completion of the Northern Pacific, the O&C imported large numbers of Chinese laborers to build its line from Portland to Roseburg in the early 1870s. Many of the Chinese who worked on the Central Pacific line moved north after 1869 to take construction jobs for the O&C.

The discovery of gold in the Powder and John Day river basins drew hundreds of Chinese to southern and eastern Oregon in the 1850s. Many Chinese immigrants were drawn to the United States by the prospect of prosperity, as well as by the desire to leave the poverty and political instability in their homes in southern China. The 1860 census reported that 425 Chinese lived in Oregon. By 1890, that number had increased to 9,540, the second largest Chinese population in the United States.

Most Chinese immigrants were young men, who sent money home to their families. Chinese women arrived in much smaller numbers. Some worked as laborers, while many more worked as prostitutes. Viewing Chinese prostitution as a national concern, Congress passed the Page Act in 1875 to prohibit the immigration of any Chinese woman who was not a merchant’s wife or who entered the country as a prostitute. It was the first federal law to restrict immigration.

With the decline of work in mining and railroads, many Chinese migrated to Portland, whose Chinatown in 1890 was second in size to San Francisco’s. By 1900, the city was home to three-quarters of the state’s Chinese population. Some operated businesses, but many were common laborers, laundrymen, dishwashers, and cooks. Others worked seasonally in canneries, farms, and lumber camps.

The anti-Chinese sentiment in Oregon and the Northwest emerged early on, especially during economic downturns such as the Panic of 1873 and the short-lived depression of the mid 1880s. The Oregon Constitution denied Chinese Americans citizenship, and there were sometimes violent antagonisms of one segment of the working class against another. When unemployment increased, white workers feared that Chinese laborers threatened their livelihoods.

The most violent “Chinese Must Go” activity in the region took place on Puget Sound, but threats against Chinese occurred in every Oregon town along the O&C line, from Portland to Roseburg. In 1886, a group of men in Oregon City expelled approximately fifty Chinese workers, and a gang of thieves murdered thirty-four Chinese miners in Hell’s Canyon in eastern Oregon the following year.

Because of animosities toward Chinese in the far western states and partly because of protests by white workers, Congress passed the Chinese Exclusion Act in 1882. The law was the first in the nation to deny naturalized citizenship to a specific nationality. While the discriminatory law greatly curbed the number of Chinese immigrants entering the United States, some continued to migrate to Oregon. When Japanese immigrants began to take place of Chinese workers in railroad construction and other labor-intensive industries, they would be subject to similar attacks.

Although the 1880 census lists only 148 Japanese in the United States, that number would swell during the next three decades, with most immigrating to the Pacific states. Many immigrated first to Hawai’i, where they worked as contract laborers on sugar plantations before moving to the mainland. Those who went to Oregon worked as contract laborers on the railroads, as workers in the fishing and logging industries, and as agricultural fieldworkers, jobs formerly held by Chinese. Mostly male, many returned to Japan and then made second or third trips to the United States.

By the early twentieth century, some Japanese had pooled their resources and started family-operated truck farms on the fringes of cities, supplying fresh fruits and vegetables to people in Portland and in Tacoma and Seattle, Washington. Koreans and Asian Indians also immigrated to the Pacific Northwest in the early twentieth century to work in agriculture, railroads, lumber mills, canneries, and mining, though they arrived in smaller numbers than the Chinese and Japanese had in the previous century.

International geopolitics singled out Japanese immigrants when Japan began to emerge as a major world power after its defeat of Russia in 1905. West Coast newspapers played up the Japanese threat and identified immigrant Japanese as a menace to American security and welfare. Corporations competing with Japan for Pacific markets helped fan anti-Japanese fears.

Most Japanese in Oregon lived in Multnomah and Hood River Counties, where they were subjected to the same abuses, injustices, and denial of civil rights that had been visited on Chinese. There was also some jealousy of the success of Japanese farmers and the so-called picture brides that joined many Japanese men after 1910. By 1920, thousands of Japanese women had immigrated to the United States through such agreements. In Oregon, the number Issei (first generation) Japanese women increased from 294 in 1910 to 1,349 in 1920.

The passage of immigration acts in 1921 and 1924 effectively ended Asian immigration to the United States, with the exception of Filipinos, as they were considered U.S. nationals and were not affected by immigration restrictions. Filipinos were employed primarily in agriculture and in canneries along the Columbia River.

The Immigration Act of 1924 also restricted the immigration of people from southern and eastern Europe. Many of those who did migrate to the Pacific Northwest during the 1880s traveled by rail cars to Portland from the Midwest. The city was home to several thousand German Americans, many arriving from San Francisco or Germany in the 1850s. Steady streams of immigrants also arrived in Portland from Great Britain, Ireland, and Scandinavia./

Beginning in the 1880s, new waves of immigrants came to Oregon from Italy, Greece, Russia, Hungary, and Poland. By 1890, 37 percent of Portland residents had been born outside the United States, the second highest percentage among major West Coast cities. By 1900, nearly 17 percent of the state’s population had been born outside the United States (the national average was 14 percent). Many of the new immigrants gravitated to specific occupations: Germans and British to urban jobs; Swedes to logging and mill work in places such as Coos Bay; Italians to truck farms; Finns to Astoria and the booming fishing industry; and Danes to towns such as Junction City, where they raised grain crops or operated dairies.

The arrival of the transcontinental in Portland in 1883 attracted African Americans to city, who took jobs as porters and dining-car waiters. When the Portland Hotel opened in 1890, African Americans were recruited from southern states to work in service jobs in the hotel. Between 1880 and 1890, the African American population in Oregon increased from 487 to 1,186. African Americans would arrive in significant numbers during the 1940s, drawn by employment opportunities created by World War II.

Between 1880 and 1910, the Northwest witnessed remarkable urbanizing trends, especially in the state of Washington. With only 10 percent of its population living in urban areas (cities and towns with 2,500 or more residents) in 1880, 53 percent of Oregon residents lived in cities and towns by 1910. The population followed a similar if less dramatic move to urban areas. Oregon was 14.8 percent urban in 1880, 26.8 percent in 1890, 32.2 percent in 1900, and 45.5 percent in 1910.

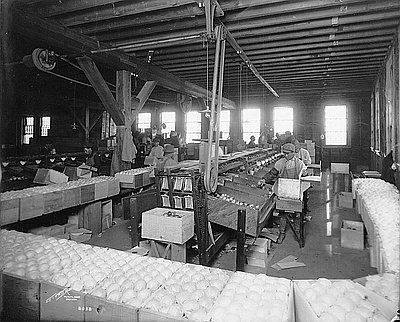

Many newcomers to Oregon between 1880 and 1910 settled Multnomah and Marion Counties. While Portland experienced a remarkable growth spurt between 1900 and 1910, other towns underwent even more dramatic increases, with Salem’s population increasing by more than 300 percent and Eugene by nearly as much. Largely because the railroad was completed through the Rogue Valley, Ashland’s population increased by nearly 200 percent and nearby Medford, a mere post office stop in 1880, grew by almost 500 percent between 1900 and 1910. The development of refrigerated rail cars contributed to a fruit-growing boom in the greater Medford area and in the Hood River valley, where populations boomed.

© William G. Robbins, 2002. Updated and revised by OE Staff, 2014.

Sections

Related Historical Records

Medford, Gateway to Crater Lake

Prior to the 1910s, most travelers to Crater Lake went by horse-drawn wagon, taking a full three days to cover the eighty-five miles from Medford. That began to …

Crating Apples in Hood River

This photograph, which shows workers packing apples into boxes, is identified by a hand-written note on the back as being “probably Hood River.” The photographer either was Benjamin …

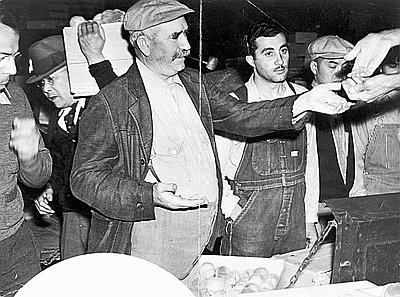

Oregon Gardeners and Ranchers Association

In this photograph, Nick Sunseri, a truck peddler, pays cash for produce at the Oregon Gardeners and Ranchers Association market, while Joe Amato looks on. Originally established about …