Rural-Urban Tensions

The ambitions and aspirations of Portland’s business community were expansive, and its publications alluded to “unoccupied” districts, “untapped” wealth, and the benefits of “opening up” new country. The city’s overweening designs had long been a part of state politics, and the tensions between urban and rural interests were manifested in legislative debates and statewide political contests.

Politicians beyond the state’s major metropolis—especially outside the Willamette Valley—distrusted Portland’s powerbrokers. The tensions between urban and rural Oregon existed, historian Earl Pomeroy argues, because “Portland was large enough to stimulate and arouse its neighbors, but not large enough to stifle them.” Those characteristics would persist into the twenty-first century.

At the turn of the twentieth century, Portland was home to a quarter of Oregon’s population. Many immigrant communities settled in Multnomah County, including Chinese, Japanese, Scandinavians, Germans, Irish, Russians, Italians, Filipinos, and Koreans. Portland was the center of the African American community; by 1920, more than 80 percent of the state’s black population resided in Multnomah County.

Mexicans first arrived in Oregon in 1851, working as mule packers who moved supplies from northern California to Oregon’s Illinois Valley. Small numbers of Mexicans migrated to southern and eastern Oregon in the nineteenth century, working as miners, railroad workers, sheep herders, merchants, and vaqueros. Railroad construction and irrigated agriculture in the Pacific Northwest presented additional employment opportunities for both Mexicans and Mexican Americans.

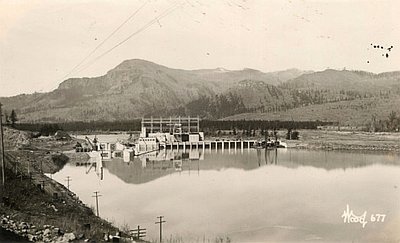

Several Mexican families settled in Malheur County in the 1920s and 1930s, following the completion of the Owyhee and Vale irrigation projects as well as the opening of a sugar factory in Nyssa./ While some Mexicans and Mexican Americans settled in the state, particularly in eastern Oregon, more of them were seasonal migrants. The onset of the Great Depression greatly reduced the number of Mexican immigrants, but the establishment in 1942 of the Mexican Farm Labor Program, known as Bracero Program, led to an increasing Mexican presence in Oregon in the second half of the twentieth century. The vast majority were part of rural Oregon.

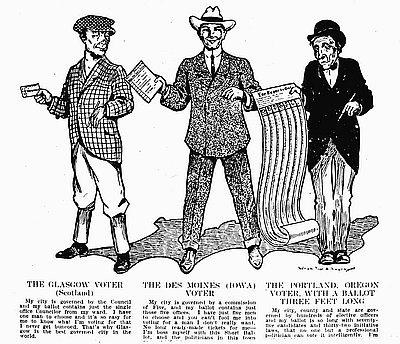

The urban-rural divide also played out in Oregon politics, and the Progressive reform movement of the early twentieth century provides some insight into how voters differed by region. Portland and Multnomah County, especially the wealthiest precincts, provided the strongest support for the direct legislation proposals of what became known as the Oregon System. In the small towns and farming communities in the Willamette Valley and in southern and eastern Oregon, direct legislation was less popular.

Urban and rural sections of the state also were divided over workplace regulations, such as the eight-hour day, child labor laws, and other restrictions on employment. Multnomah County ranked first in support of such legislation, but voters were lukewarm toward such measures beyond the Portland area.

There were also divisions over social conformity proposals, with Prohibition more popular in rural sections of the state than it was in Multnomah County. Rural voters supported social legislation that upheld the traditional cultural values of white, Anglo-Saxon Protestantism. Such tendencies placed the state at the center of nativist sentiments during the 1920s with the rise of the Ku Klux Klan.With a few exceptions, the initiative measures that rural voters supported often discriminated against racial and religious minorities. The reverse was true of the 1923 Oregon School Bill initiative, which faced considerable opposition in central and eastern Oregon. For the most part, however, Oregon was no different from other states, where resistance to social and cultural change is typically strongest in the countryside.

© William G. Robbins, 2002. Updated and revised by OE Staff, 2014.

Sections

Related Historical Records

Mexican Laborers Weed Sugar Beet Field

This photograph shows Mexican citizens weeding and thinning in an unidentified sugar beet field in Oregon, probably in Malheur County, during World War II. In 1942, the United …

Oregon System Cartoon

This political cartoon from Joseph Gaston’s Centennial History of Oregon depicts a befuddled Portland voter holding a lengthy ballot in one hand standing next to two other men …

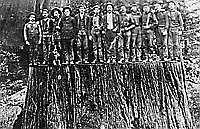

Scandinavian Immigration

This undated photograph of a group in Scandinavian costumes was taken in Portland by a photographer documented only as “Erickson.” Between 1820 and 1920, more than 2.1 million …