Roads to Freeways: Building and Land Preservation

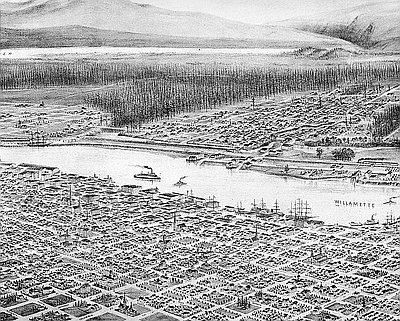

The construction of multilane highways dated from the 1930s, with the construction of Barbur Boulevard—running south from Portland on the route of an abandoned electric interurban railroad—and McLoughlin Boulevard. As the modern descendants of the east-side and west-side Indian trails up the Willamette Valley, these were respectively federal highways 99E and 99W. The congressional mandate for the interstate highway system in 1956 began a two-decade period of massive freeway construction. The freeway routes ran along the northern and northeastern edges of the state (I-84), around and through the city of Portland (I-205, I-405), and from Portland south through the Willamette, Umpqua, and Rogue River valleys to California (I-5). The freeway infrastructure—characterized by massive fills and cuts, huge bridges, and immense traffic interchanges—re-oriented the state’s economy. The transportation framework became concrete corridors that paralleled the earlier railroad routes but were very different in their workings and their impact on the built environment. Native trails, early roads, and railroads followed natural contours. Modern motor vehicles could climb a percent grade, three times that of a moderate railroad grade; modern earthmoving equipment made it economically possible to re-arrange the landscape to suit the roadway.

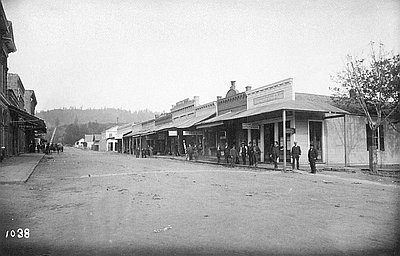

The spreading suburbs, highway construction, and population growth helped fuel the nascent historic preservation movement in the 1960s. The loss of familiar structures also contributed, as Oregonians saw the destruction of dozens of wooden covered bridges and of the Portland Hotel. The historic preservation movement came of age with the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966 and was highlighted that same year by the designation of the gold-rush-era town of Jacksonville, Oregon, as a National Historic Landmark. Preservation efforts soon touched Astoria, Albany, Aurora, Ashland, Portland, and many other communities. Concerns about preserving the built environment meshed with a growing awareness of the vulnerability of many of the state’s natural resources to human exploitation and degradation, helping to inspire Oregon’s pioneering political efforts in land conservation and planning in the 1970s.

© Richard H. Engeman, 2005. Updated by OHP staff, 2014.

Sections

Native Ways and Explorers' Views before 1800

Euro-American Adaptation and Importation

Sawn Lumber and Greek Temples, 1850-1870

Architectural Fashions and Industrial Pragmatism, 1865-1900

Revival Styles and Highway Alignment, 1890-1940

International, Northwest, and Cryptic Styles

Glossary

Built Environment Bibliography

Related Historical Records

California Street, Jacksonville, c1890

This photograph looks west on Jacksonville’s main business street, California Street, about 1885. The photographer, Swiss-born Peter Britt, arrived in Jacksonville in 1852 to mine for gold, but …

Article, I-5 Now Completed throughout Oregon

The interstate highway system changed the face of America. Although Congress had been discussing the development of an interregional highway system since the 1930s, construction of this massive …