Surveyed Patterns on the Land

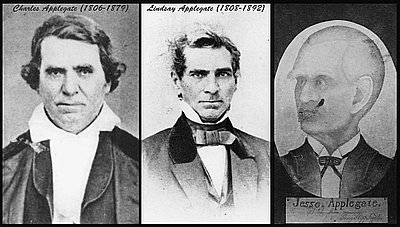

Euro-American settlers in the Willamette Valley of the 1830s and 1840s had no instructions to follow in selecting their farmland. They observed that prairie lands required little clearing before they could be tilled, and they knew they needed some timbered land to supply building materials and fuel. Being on or near a navigable stream made transportation easier, and a dependable spring was needed for fresh water. The farms were often quite large and were only partially defined by firm boundaries. Not until after the American creation of the Oregon Territory were there means to legally describe and claim title to land.

The passage of the Donation Land Act of 1850 established a system of surveying for the Oregon Territory. Using the township system first laid out in the Land Ordinance of 1785, federal surveyors placed an imagined north-south grid over the Willamette Valley. The grid soon extended to other settled areas in the Rogue and Umpqua River valleys, and eventually to the entire state. Existing land claims were validated through this process, while new claims were created from the remaining pieces, pressed into the mold of the survey grid.

Historic maps reveal the result of this interplay of topography with survey lines. While historic trails and roads are shaped by topography, property boundaries became tied to the survey grid. To minimize the impact on property owners, later roads often follow property lines, regardless of intervening creeks or hills. A typical farm consisted of farmhouse, barn, outbuildings, and fenced fields, and farming frequently involved channeling creeks, draining marshes, and cutting groves of oak trees. Huge fields of a single crop, such as wheat, replaced a variety of native vegetation, and domestic cattle and pigs displaced native ducks and beaver. The Kalapuyans had used and manipulated the natural resources of the Willamette Valley, but the impact of Euro-American farming on the landscape was rapid and radical.

Indian trails had been developed for foot traffic. By the early nineteenth century, they were being shaped into trails for horses in northeastern Oregon, a practice that quickly spread throughout the region. Riding and packing freight by horse gave way to the development of wagon travel in the 1830s and 1840s, most notably along the Oregon Trail and its offshoots. For wagons, narrow, steep trails had to be altered to reduce the grades and to avoid or remove obstacles. Trails grew into roads.

Rivers were traditional arteries of commerce, but for horses and wagons they became a barrier to travel. There were informal canoe ferries as early as the 1830s, often operated by Indian boatmen. These began to be supplanted by specially built wooden ferries in the 1840s, powered by the river’s current. Log bridges were makeshift but easy to build. Howard Corning’s Dictionary of Oregon History reports that the first bridge in Oregon might have been a log structure erected across Dairy Creek in Washington County in 1846, but very likely there were earlier examples. More sophisticated timber spans crossed the Yamhill River at Lafayette in 1851, and a planked bridge spanned the Marys River at Corvallis in 1856. Covered bridges made their first appearance in the 1850s, when the wooden trusses that supported the span were sheathed in wood boards to protect them from rain and rot. Oregon continued to build covered wooden bridges into the 1940s.

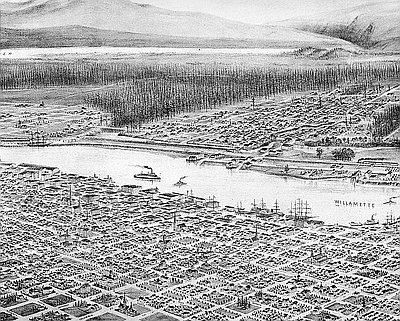

Ferry landings also became points for the transshipment of goods from road to river, as wheat and other farm crops began to move down the Willamette River for export and imported goods came upriver in return. Small settlements such as Champoeg, La Butte (later Butteville), Fairfield Landing, and Lincoln dotted its banks. Their stories are chronicled in Howard McKinley Corning’s Willamette Landings: Ghost Towns of the River. The viability of these towns varied not only with changing crops and methods of transportation, but also with the fickle forces of the river itself, which typically flooded during winter rains and the spring runoff and often changed course, leaving a once-thriving landing on a sluggish slough as the main channel moved to another course. With the decline of river transportation, landings and ferries became less important points. Where bridges supplanted landings, such as at Dayton and Independence, communities endured, but the focus of their activities moved away from the river.

© Richard H. Engeman, 2005. Updated by OHP staff, 2014.

Sections

Native Ways and Explorers' Views before 1800

Euro-American Adaptation and Importation

Sawn Lumber and Greek Temples, 1850-1870

Architectural Fashions and Industrial Pragmatism, 1865-1900

Revival Styles and Highway Alignment, 1890-1940

International, Northwest, and Cryptic Styles

Glossary