Town Beginnings

The Oregon landscape of the 1840s had a number of scattered Indian communities, and other small settlements of diverse population at places such as The Dalles, Astoria, and Salem. Most of the immigrant population that had come from the Midwest was engaged in farming, especially in the Willamette Valley. But a number of immigrants brought with them skills and trades that were suited to city life, and towns and cities began to develop in Oregon at a very early date.

The need to import manufactured goods by sea and the development of an agricultural surplus for export dictated the establishment of port facilities at some point on the Columbia River system. An early contender was Oregon City at Willamette Falls. Here John McLoughlin, chief factor of the Hudson’s Bay Company post at Fort Vancouver, surveyed a town site in 1842-1843, a single street parallel to the river and flanked by nine blocks of building lots. While some sailing vessels had reached Oregon City, it soon became apparent that the rapids at the mouth of the Clackamas River and other shoals were major obstacles to navigation. Still, Oregon City flourished during the 1840s as a milling and trading center and seat of local government, supported in part by its fond hope of becoming a major seaport.

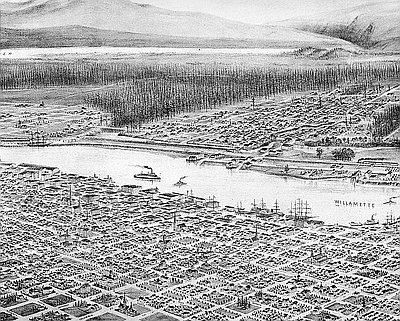

Several other landholders promoted townsites that they hoped would become major port cities. An essential aspect of the city-building impulse was the platting and selling of land. Developers subdivided their property into small parcels of blocks and lots and dedicated streets for a permanent public right of way. The purchase and development of lots by ship owners, exporters and importers, and merchants helped propel the development of prospective port cities. Among the contending townsites were Linnton (1844; now part of Portland), Milwaukie (1848), and St. Helens (1850). It was a combination of circumstances that brought Portland to prominence as the regional port during the 1850s and 1860s: a good road to the highly productive wheat fields of the Tualatin Plains, sufficient level land for port facilities, a site near the head of navigation for sea-going vessels, and entrepreneurship.

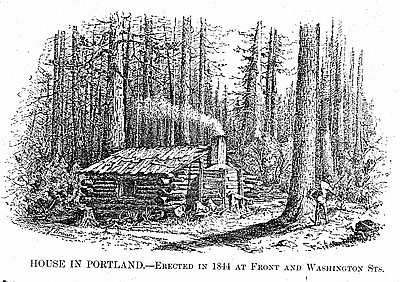

Portland’s rise was rapid. The initial townsite was platted by Asa Lovejoy and Francis Pettygrove in 1845, with streets paralleling the west-side riverbank, between today’s Washington and Jefferson streets. To promote their town, Lovejoy and Pettygrove sold lots inexpensively and even gave them away to some who agreed to build a cabin. Pettygrove built a warehouse, wharf, and store at the foot of Washington Street in 1846, along with the town’s first wood frame house.

Portland’s status as the head of navigation and an up-and-coming port city was forwarded by two notable early captains, Capt. John Couch of the brig Chenamus, who established a land claim just north of the Pettygrove claim—the site of Portland’s present Skidmore/Old Town Historic District—and Capt. Nathaniel Crosby, Jr., of the bark Toulon, which began regular trading with Hawai’i. Capt. Crosby erected a prefabricated house in Portland in 1847. The lumber had been cut to measure in Boston and shipped to Honolulu, then aboard the Toulon to Portland—an instant New England dwelling in both style and materials. Although a number of similar prefabricated houses were shipped to California from the East Coast during the gold-rush period, this was an unusual occurrence in Oregon. Capt. Crosby’s imported house was a novelty, not a trend-setter.

The blocks in Portland’s first town plat were 200 feet square, with streets 60 or 80 feet wide and standard lots 50 by 100 feet. The hundreds of subsequent additions to this first plat showed a myriad of variations to the pattern, but the narrow streets and 50 by 100 lot size became common features citywide. Later plats in the Portland area also tended to adhere to the cardinal points of the compass rather than the river orientation of the first survey. Plats for other early Oregon townsites show a similar tendency to use a basic grid that is oriented to an existing stream or road. With the rapid surveying of the state in the 1850s and 1860s, town plats quickly shifted to a north-south orientation. The patterns of development fostered by townsite plats have proven to be enduring aspects of our built environment.

The largest number of American settlers who streamed into Oregon in the 1840s and 1850s headed first for the fertile Willamette Valley. Other areas that attracted family farmers included the Rogue River and Bear Creek valleys of southern Oregon, the Umpqua River and Yoncalla valleys north of the Rogue, and Clatsop Plains south of Astoria. Many of the immigrant farmers had basic skills in building with wood, and the newcomers included artisans who specialized in carpentry, masonry, and other building trades. The professions of architecture and structural engineering were in their infancy, so the buildings and other structures erected in Oregon before 1870 were almost entirely designed and erected by carpenter-builders who had learned their skills on the job. The general term for such construction is vernacular—buildings that are common to the place and period.

Two basic framing techniques were central to vernacular construction in Oregon. The traditional hewn timber frame building was held together with wooden pegs, a technique that was easily adapted to Oregon materials and conditions. The newer wood construction method known as the balloon frame substituted a strong but lightweight framework of sawn lumber that was held together with nails. Both methods were in use by the 1860s. The balloon frame—faster and easier to build—quickly came to dominate residential construction, and it did so for more than a century.

Carpenter-builders brought with them not only construction techniques but also concepts about the layout, or plan, of buildings and their appearance. Many of the farmhouses built in the 1840s and 1850s have been described by architectural historian Rosalind Clark as “Colonial and Federal survivors,” because they were stylistically some years behind the current practices of New England. Some early Oregon houses, for example, had two exterior doors opening on a covered porch extending across the front of the house. In effect, the front porch was an outside hallway connecting the two front rooms, a fashion that immigrants from the East Coast brought with them, along with newer modes such as the plan that provided a central hallway from the front door, with rooms to each side.

The architectural style known as Classical Revival was very popular in the Oregon of the 1850s and 1860s and was easily carried out by carpenter-builders. The Classical Revival style was favored not only for residences but also for schools, churches, and even stores. It was derived from Greek design elements that had originally been executed in stone and was characterized by columns supporting the porches or pilasters marking the building corners. It often featured a formal entablature at the roofline, consisting of architrave, frieze, and cornice. The gable roof had eave returns or pedimented gables that contributed to the temple effect that was a key element of the style. The main façade was often marked by the bilateral symmetry of windows and doors. The adaptation of this style to wooden buildings proved to be quite successful. It was difficult to emulate smooth stone walls in wood, but narrow horizontal clapboard siding—initially painted in colors, but often later simply white—gave satisfaction.

The Classical Revival style interpreted in wood resulted in Oregon farmhouses and town streetscapes that displayed qualities of antiquity and substance, despite the newness of their construction. Travelers reported that Oregon towns and farms much resembled those of staid New England. Oregon’s built environment in the mid-nineteenth century rarely displayed the latest in architectural fashion, but instead exhibited the imported skills and persistent ideas of the immigrant carpenter-builders.

© Richard H. Engeman, 2005. Updated by OHP staff, 2014.

Sections

Native Ways and Explorers' Views before 1800

Euro-American Adaptation and Importation

Sawn Lumber and Greek Temples, 1850-1870

Architectural Fashions and Industrial Pragmatism, 1865-1900

Revival Styles and Highway Alignment, 1890-1940

International, Northwest, and Cryptic Styles

Glossary

Built Environment Bibliography

Related Historical Records

Hudson's Bay Company Blanket

White blankets like this Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC) blanket were among the first to be traded among fur trappers and Native Americans in North America. They were especially …

Overton Cabin

One of the first dwellings in Portland, this cabin was named for William Overton. In late 1843, Native American guides took Overton and his companion, Asa Lovejoy, to “the …

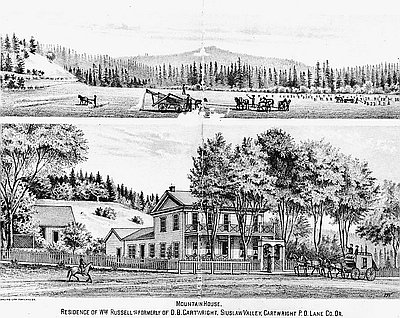

Cartwright House (Mountain House)

The lithograph above is derived from a sketch of Mountain House, a landmark farm and stage stop along the California-Oregon Trail. The house was built in 1853-1855 by …