World War II Opens New Doors

During World War II, the availability of inexpensive hydroelectric power from new dams at Bonneville and Grand Coulee propelled the development of heavy industry in Oregon in ways not previously imagined. Shipbuilding had long been established in the Portland and Astoria areas. As had happened in 1917, war caused a sudden need for military and support vessels, but this time on an unprecedented scale. Oregon saw the creation of new industries such as aluminum production and aircraft parts manufacture and the expansion of established industries such as timber production. These activities impelled the construction—with limited materials and under tight time constraints—of huge new factories, especially in the Portland area. Military camps sprouted in the Willamette Valley at Camp Adair, in southern Oregon at Camp White, and in other facilities near Klamath Falls, Pendleton, Tillamook, and Bend. To serve the influx of thousands of shipyard workers who migrated from other parts of the nation, Vanport City north of Portland was built in 1942, with permits issued in August and the first people moving into apartments in December.

Other infrastructure construction was nearly halted unless it was related to the war effort. In the 1930s, the state had lavished money and effort on the Oregon Coast Highway, which was meant to improve commerce between coastal points and to support tourist travel. It was nearly completed when the war began and construction stopped. Highway building continued on only a few projects, such as the completion of the Wolf Creek—now Sunset—Highway connecting Portland with the military facilities at Camp Rilea, Fort Stevens, and Tongue Point in Astoria.

It was expected that much of the wartime activity would have only a temporary impact on the landscape. Camp Adair, located north of Corvallis on some 50,000 acres of long-settled farmland and in the hills of the Coast Range to the west, was hurriedly built in 1942 to train army infantry troops for European service. After it was decommissioned in 1946, remnants of the main post facilities lived on as Adair Village—postwar housing for students and faculty at nearby Oregon State College—and as part of an air force facility and private housing for many years. The camp’s imprint is still very visible, while other traces persist in local buildings that were moved off the campsite and converted to other uses. The camp’s function as a battle training ground permanently erased many pioneer farmsteads and relocated highways, a railroad, and several small communities.

Other military projects had similar repercussions, leaving a legacy of hastily built wooden barracks and residences that served for many years beyond their intended lifetime. The U.S. Navy blimp hangars in Tillamook were two cavernous structures supported by Douglas fir wood trusses, measuring an unobstructed 195 feet in height, 296 feet wide, and 1,086 feet long—a record for wood construction. Built of wood because of the wartime steel shortage, the hangars were prototypes for seventeen such structures around the nation. After the war, the Tillamook hangars housed lumber planing operations and other industrial activities; one remains in use today as a museum. War-related housing projects at Guild’s Lake and Ardenwald in the Portland area survived for some years, as did Navy Heights in Astoria. The Marine Corps barracks near Klamath Falls were the first home of the Oregon Technical Institute—now the Oregon Institute of Technology—and the officers’ club at Camp Abbott became the Great Hall at the sprawling postwar (1969) resort development known as Sunriver.

The exigencies of wartime construction dictated quick, simple, inexpensive, unadorned buildings that used as little as possible of scarce materials such as metal, lumber, and glass. Buildings constructed during the war years and immediately after, when shortages still existed, were often characterized by reduced-pitch gable or shed roofs, short eaves, and small windows, along with compact floor plans and no basements. In the interest of speed, builders often used green or unseasoned wood that warped and shrank as it aged, producing buildings that soon needed repairs and rebuilding. The needs of the moment were all that could be considered.

© Richard H. Engeman, 2005. Updated by OHP staff, 2014.

Sections

Native Ways and Explorers' Views before 1800

Euro-American Adaptation and Importation

Sawn Lumber and Greek Temples, 1850-1870

Architectural Fashions and Industrial Pragmatism, 1865-1900

Revival Styles and Highway Alignment, 1890-1940

International, Northwest, and Cryptic Styles

Glossary

Built Environment Bibliography

Related Historical Records

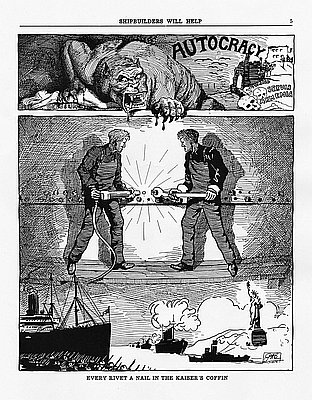

Shipbuilders Will Help

This illustration was published in a short-lived weekly newspaper produced by the Columbia River Shipbuilding Corporation (CRSC). Win the War, later renamed The Pilot, was issued in 1918 …

Nightshift Arrives Portland Shipbuilding

During World War II, up to 125,000 people worked in around-the-clock shifts at shipyards in Portland and Vancouver, Washington. This photograph, taken by Ray Atkeson, shows nightshift workers …

Iona Murphy at Oregon Shipbuilding Corp., Portland

This ca. 1943 photograph, taken by Ray Atkeson, shows Iona Murphy welding in an assembly building at the Oregon Shipbuilding Corporation in Portland. During World War II, up …