Industry and Agriculture in the Railroad Era

The completion of railroad links to California and the East during the 1880s brought new building materials and ideas to Oregon and provided a means of exporting products to a wider market. Railroads also brought a new infrastructure in the form of the railroad track itself and the associated bridges, tunnels, stations, warehouses, roundhouses to stable locomotives, and workshops to repair equipment. The new opportunities for shipping by rail led to the building of distribution warehouses, while railroad-served markets caused the construction of lumber mills and grain elevators next to the tracks. In the 1880s, stationary steam engines freed mills from a dependency on falling water to provide power. Manufacturing could now take place most anywhere.

Oregon’s natural resource industries boomed. New crops supplemented such reliables as wheat and apples. Prunes, walnuts, and hops, which found favor in the Willamette Valley, were dehydrated for preservation and shipping in a distinctive building form, the dryer. New canning technology boosted the construction of fruit and vegetable canneries and of dozens of fish canneries on the Rogue and Columbia rivers, where salmon was canned for a worldwide market.

The growing timber industry required specialized equipment, from axes and hand saws to locomotives and stationary boilers, band saws, winches, and wire cable. The equipment was manufactured in eastern industrial regions, but Oregon manufacturers soon began to import partially finished materials and to construct the equipment locally, often making modifications to suit local conditions. The discovery of deposits of soft coal—mined commercially near Coos Bay—and iron ore near Lake Oswego, prompted the creation of a local iron and steel industry, although those efforts were unsuccessful.

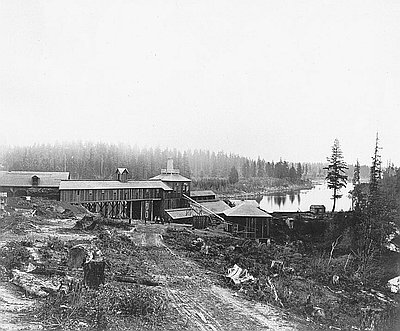

Buildings and structures for mining, milling, and manufacturing were usually designed and built of wood in the vernacular tradition. The job of building engineer—like architecture, an occupation that was rapidly professionalizing—played a major role in railroad construction and in the construction of bridges, wharves, and fish canneries, but few trained architects engaged in such work. The buildings that went up along the hundreds of miles of new railroad track were utilitarian and unadorned, much like the wharves and docks that served river and ocean transportation.

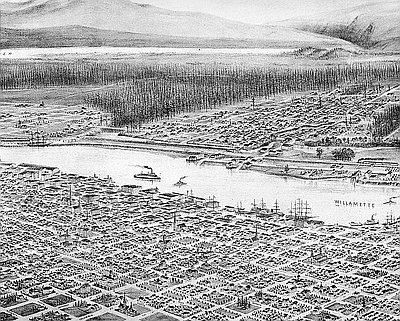

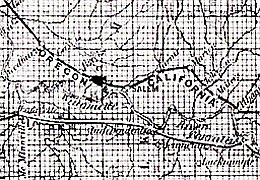

The railroads had a major impact on the state’s built environment. Early construction such as the Oregon & California Railroad line that linked Portland with Roseburg in 1874 was built as inexpensively as possible. Still, the line required major bridges across the Clackamas, Santiam, McKenzie, Willamette, and Umpqua rivers, first of wood and later replaced with iron and steel. The crossing of the Siskiyou Mountains into California required numerous tunnels and miles of wooden trestlework. By 1900, locomotive roundhouses, workshops, and freight yards operated in Portland, Albany, Eugene, and Roseburg along the Southern Pacific’s former O&C line, as well as passenger and freight stations, water-supply tanks, and fueling facilities. The railroad companies developed standard plans for many of their facilities, so that Southern Pacific stations and structures in towns such as Oregon City and Central Point looked much the same and were painted in standard company colors—a mustard yellow with brown trim.

© Richard H. Engeman, 2005. Updated by OHP staff, 2014.

Sections

Native Ways and Explorers' Views before 1800

Euro-American Adaptation and Importation

Sawn Lumber and Greek Temples, 1850-1870

Architectural Fashions and Industrial Pragmatism, 1865-1900

Revival Styles and Highway Alignment, 1890-1940

International, Northwest, and Cryptic Styles

Glossary

Built Environment Bibliography

Related Historical Records

Oregon and California Railroad

The Oregon and California Railroad (O&C) was the first railroad to connect Oregon with California. Construction of the line began in Portland during the spring of 1868. Under …

Oswego Iron Works

In 1867, workers smelted the first iron ingots produced at the Oregon Iron Company at the confluence of the Willamette River and Sucker Creek, now known as Oswego …

Chinese Workers in Astoria Cannery

This undated photograph of the interior of an Astoria cannery is from the Burlington Northern / Spokane Portland and Seattle Railroad Collection. This promotional photograph conveys the message …