Fort Klamath and the Road to Bloody Point

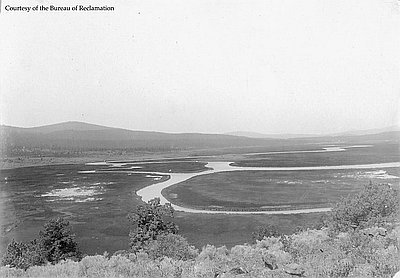

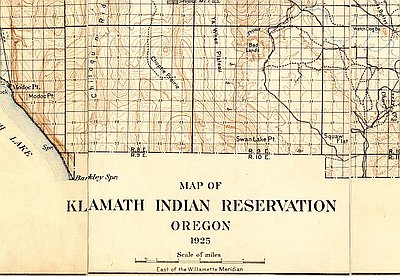

During the Civil War, the Oregon legislature asked Congress for a military post to keep the Indians of the Upper Klamath Basin under control. In March 1863 Major C. S. Drew surveyed the sites that had been recommended for the new fort. One was not far from the Applegate Trail where emigrants needed protection; another, overlooking the Link River, lay within the boundaries of today’s Klamath Falls; the third was in Wood River Valley north of Upper Klamath Lake. Although this northernmost site was farthest from Bloody Point where emigrants had been killed, Major Drew considered it the best. In addition to having abundant water, ample grass to feed horses and mules, and an extensive pine forest to provide fuel and building materials, this was where the Oregon Central Military Road met the trail between the Rogue River Valley and the mines east of the Cascades.

Trout and mullet crowded the lakes and streams, and elk, antelope, ducks, geese, and other game offered hunters countless targets. Yet food became a problem once the fort was garrisoned. Long, snow-clad winters isolated Fort Klamath, blocking the supply routes from the California coast and the Rogue River Valley. Indians taught soldiers how to spear fish through ice, but winter fare was rarely fresh. Men dined on dry bread and potato meal, boiled chunks of formerly frozen beefsteak, two-inch-thick squares of “mixed vegetables,” and coffee.

With Linkville—later Klamath Falls—thirty-six miles to the south and Jacksonville 100 miles west across the mountains, loneliness and boredom plagued the soldiers. Some ran off, attracted by dreams of gold. If captured, a deserter was court-martialed. If found guilty, he was tattooed with a “D” on his left hip.

The major problem the soldiers had to contend with was Indians leaving the reservation. Members of the Yahooskin “Snake” tribe ran off the year the treaty was signed. Captain Jack’s band of Modocs left in 1870. Because the Modocs returned to their territory south of Klamath Falls, soldiers at the fort were poorly positioned to protect settlers from Indians and Indians from settlers.

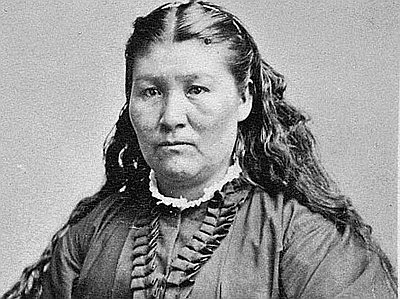

Like various tribes in the Pacific Northwest, the Modocs raided other tribes and took slaves. This gave them an advantage over indigenous Californians to the south of the Klamath Basin who avoided combat and neither used nor traded slaves.

Unfortunately for the Modocs, in 1846 a more dominant tribe appeared on their horizon. That year John Charles Frémont made his fatal foray at Upper Klamath Lake and the Applegate Trail opened, passing through Modoc territory. Trying to stop the flow of emigrants, Modocs attacked wagon trains. Their weapons, however, could not stop the smallest and most lethal invaders: in 1847, at least 150 Modocs died of smallpox.

Traffic over the emigrant route grew in 1849, bringing gold-seekers as well as settlers. The following year one Modoc assault at the northeastern shore of Tule Lake killed eighty people and inspired a name that would haunt the region: Bloody Point.

This massacre gave the Modocs a reputation. Whenever Indians raided a miner’s pack train, Modocs were blamed. In 1851 a band of Indians, possibly from the Pit Rivers Tribe, ran off with forty-six mules and horses that miners were bringing into the gold fields. A posse formed to retrieve the animals. Led by Ben Wright, a seasoned Indian fighter, these vigilantes sneaked into a Modoc village, captured women and children, and killed several men.

Modoc attacks at Bloody Point continued. A Ben Wright rescue party broke up one attack against a wagon train. In 1852 Wright set up camp near a Modoc village on Lost River. With his men hidden nearby, Wright walked into the village, a pistol concealed beneath his serape, and shot the headman. His men opened fire. Only five of more than forty Modocs escaped.

The Ben Wright massacre put an end to the Modoc raids, but presaged the tragic Modoc War that broke out twenty years later.

© Stephen Most, 2003. Updated by OHP staff, 2014.

Sections

Related Historical Records

Fort Klamath

Colonel C. S. Drew, First Oregon Cavalry, was sent in 1862 to scout a location for an Army post to protect settlers in the new West. The site, …

Ben Wright Massacre of 1852

These two accounts of the same event, one written by a white pioneer, the other by the son of a Modoc woman and a white settler, serve as excellent …

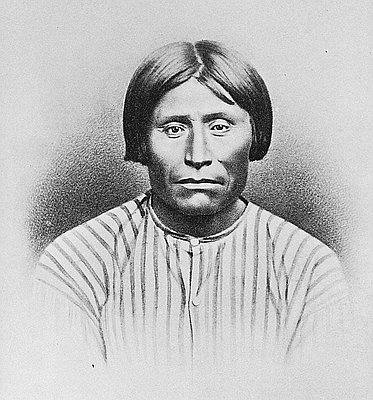

Kintpuash (Captain Jack)

Kintpuash (also spelled Keintpoos, Keiintoposes), better known as Captain Jack, was a Modoc Indian chief during the 1860s and early 1870s. In a desperate attempt to maintain his …