Living in and Reclaiming the Basin

In 1852, a brave nineteen-year-old Wallace Baldwin drove fifty head of horses from the Rogue River Valley into the Klamath Basin. He had packed only enough food for his trip along the Applegate Trail, and he had no gun. Klamath Indians helped him survive. They brought him game and taught him how to eat epaw, the tuber that was their potato. Baldwin found fertile ground for pasturing his horses and a sunny climate. Although it is unknown how long he stayed, the young man is considered the first non-Indian settler in Klamath country.

Fifteen years later, George Nurse, a civilian who supplied Fort Klamath with goods, built a small store near the Link River and stocked it with a wagonload of trinkets and necessities. In May 1867 he established a ferry service across Link River on the trail between the fort and Yreka, California. Soon buildings clustered from the hillside on the north to the swamps on the south and east.

A saloon, a harness shop, and a United States Land Office were among Linkville’s early attractions. A pack train brought supplies from Yreka; a stage service provided weekly mail delivery from Ashland. Travelers tied their horses to the hitching post in front of Nurse’s Hotel.

In 1873 the Modoc War made the town famous across the United States; journalists stayed in the hotel. By 1885 the population had climbed to 384. There were four saloons, three hotels, seven stores, three blacksmith shops, a butcher shop, one newspaper, four doctors, four lawyers, a telegraph office, a Presbyterian church, a flour mill, and a jail. Courtroom space was rented until 1888 when a courthouse and a new jail were built, each costing about $3,500.

In 1891 disaster struck. A fire wiped out the buildings near the river. The town was rebuilt, and with its renewal came a campaign to rename Linkville. Two years later a new city charter named the town Klamath Falls. This name not only suggested a bigger town than any “ville” could be, it connoted the modernity of water power and electricity. Shortly thereafter a dam was built where the upper lake spills into Link River, obliterating the falls at Klamath Falls.

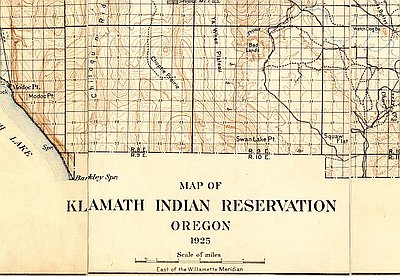

In the second half of the nineteenth century, populating the western states was a federal priority. Nationally subsidized transcontinental railroads brought people to the West; the allotment of homesteads on unoccupied lands and Indian reservations provided living space and goods. Still, most of this country was arid. Without ample food and water, there could be no home on the range.

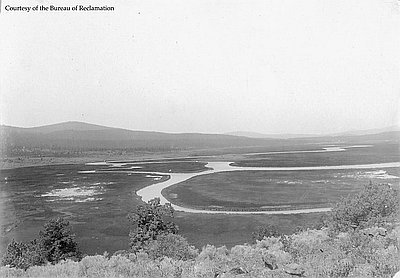

At the beginning of the twentieth century, the nationalization of waterways to provide irrigation, flood control, water storage, and power addressed the problem of supporting the West’s growing population. One of the first projects of the new Bureau of Reclamation helped settlers farm lands where water interfered with cultivation: the marshy, lake-rich terrain of the Upper Klamath Basin and the Lost River drainage.

In order to drain the lakes and marshes and develop a system for moving these waters, the Bureau required the states of Oregon and California to cede to the federal government its rights and title to the region of Tule Lake and the Lower Klamath Lake.

Originally, the reclaimed lands were to be sold in 80-acre homesteads. Payments would then subsidize reclamation of other lands. Yet the Bureau neither pressed farmers for their payments nor penalized those who farmed more lands than were allowed. New congressional appropriations provided what the Bureau needed to generate new projects and, in the Klamath Basin, to build headgates, irrigation canals, ditches, sumps, dams, reservoirs, hydroelectric turbines, and pumps to move the water.

After World War I, Klamath Project plots were given to veterans who applied for them. In the 1920s and 1930s there was more Project land than people who wanted to farm it.

World War II veterans competed for Klamath Project farms by participating in a lottery. Those who won got a great deal. In addition to providing free land and supplying water, the government compensated for the low prices farmers received for many crops. As a result, the Upper Basin remains one of the few regions in the United States where families rather than agribusiness corporations run the farms. By the end of the twentieth century, there were approximately 1,400 farms on the Klamath Project, cultivating up to 210,000 acres.

© Stephen Most, 2003. Updated by OHP staff, 2014.

Sections

Related Historical Records

Klamath Indians in Dugout Canoes

The Klamath Indians traditionally lived in villages and seasonal camps in southern Oregon, near upper Klamath Lake, Klamath Marsh, and the lower Williamson River. Canoes were very important …

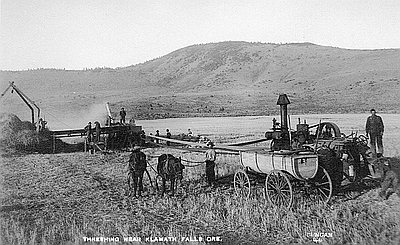

Threshing near Klamath Falls

This postcard shows farmers using a steam-powered thresher near Klamath Falls, which was originally called Linkville. In 1909, the Southern Pacific Railroad reached Klamath Falls, helping attract more …