Losses and Gains for Tribes

As reservation lands dwindled during the late nineteenth century, Native Americans moved to places where they could make a living, working as hop pickers, trappers, farm workers, small farmers, loggers, millhands, and domestics. In 1898, the Clatsop and Tillamook tribes were the first to try to make the federal government pay for the lands it had taken. Their attorney was Silas Smith, grandson of the Clatsop headman Coboway, who had greeted Lewis and Clark at the mouth of the Columbia in 1806. In 1907, the Tillamook and two other lower Columbia tribes were awarded $23,500 in compensation.

Over the next four decades, several Indian groups brought claims against the United States, most of them unsuccessful. The Coos, Lower Umpqua, and Siuslaw lost a twenty-year struggle to gain compensation for the lands taken in their unratified treaty. The court ruled that tribal members could not prove they had ever owned any land before some of them took up individual allotments in 1892.

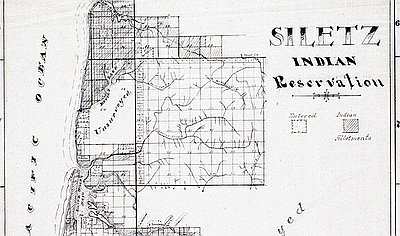

Of thirty-two western Oregon groups that had filed claims jointly, the Coquille, Tututni, and Chetco were designated as “tribes” and won awards. The others, including the Chinook, Clatsop, Nehalem band of Tillamook, Confederated Tribes of the Grand Ronde Community, and Siletz Confederated Tribes of Indians, were denied, although the Tillamook and Nehalem band of Tillamook won awards in 1955 for land ceded from the Siletz Reservation. Of the groups whose treaties had been ratified by Congress, only the Molala and the Umpqua and Calapooia bands of the Umpqua Valley won monetary awards.

In 1954, under a policy called termination, the federal government unilaterally dissolved its relationship with certain groups that had existed since the signing of the treaties in the 1850s. More than half of the 109 tribes and bands that were terminated had their ancestral homelands in Oregon. The avowed goal of the policy was to emancipate Indians so that they could become assimilated into mainstream society. A few tribal groups endorsed termination, but many opposed it. In practice, termination damaged the tribes culturally, politically, and economically.

Since the 1970s, tribal governments have become more systematic and organized about gaining political power, and several of the terminated tribes succeeded in winning back the trust relationship with the U.S. government. Restoration was a tedious process. A tribe had to secure a champion in Congress to sponsor legislation on its behalf, and it had to prove that it had been a tribe continuously since before white contact. The Confederated Tribes of Siletz Indians was restored to tribal status in 1977 and received a 3,730-acre reservation in 1980. The Cow Creek Band of Umpqua Tribe of Indians was federally recognized in 1982. The Confederated Tribes of Grand Ronde was restored in 1983 and received a 9,811-acre reservation in 1988. The Confederated Tribes of Coos, Lower Umpqua, and Siuslaw was restored in 1984 and kept the 6.1-acre parcel in Coos Bay that they had refused to yield during termination. The Coquille Tribe was restored in 1989.

Since restoration, some of the tribes have developed significant economic enterprises. The Coquille Tribe, for example, is the second largest employer in Coos County, with business ventures in forestry, gaming and hospitality, assisted living and memory care, telecommunications, renewable energy, and a cranberry farm. The Confederated Tribes of Coos, Lower Umpqua, and Siuslaw, headquartered in Coos Bay and with offices in Florence, is working on reclaiming some of its ancestral lands now held by the federal government. In 2005, the Tribes regained ownership of forty-three acres on Coos Head, the site of a former U.S. Navy and Air National Guard station, on which they constructed facilities to support tribal government programs. The Confederated Tribes of Siletz operate and manage several businesses and commercial properties in Lincoln City, Eugene, Salem, and Portland.

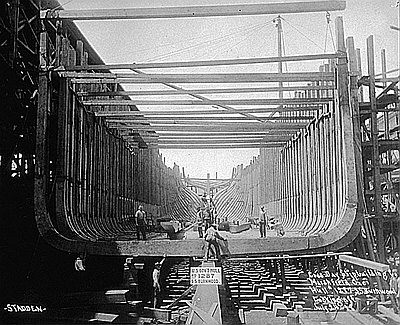

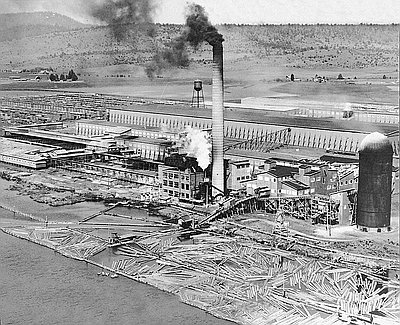

In 1988, Congress passed the National Indian Gaming Regulatory Act, which made it legal for tribes to operate casinos on trust lands. An important component of the Conquille’s business operations is The Mill, a casino and hotel on the North Bend bayfront, built between 1995 and 2000 on the site of a shuttered Weyerhaeuser sawmill. In 1995, the Confederated Tribes of Siletz opened Chinook Winds Casino Resort in Lincoln City. Also that year, the Confederated Tribes of Grand Ronde opened Spirit Mountain Casino, the center of the Tribes economic development program and the most successful casino in Oregon. In 2004, the Confederated Tribes of Coos, Lower Umpqua, and Siuslaw built the Three Rivers Casino in Florence. Three years later, they expanded the property to include a hotel. The facility is currently one of the area’s largest employers.

© Gail Wells, 2006. Updated and revised by OHP staff, 2014.

Sections

Related Historical Records

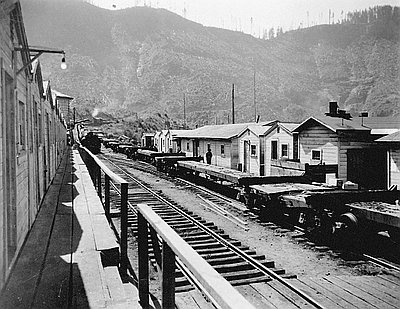

Weyerhaeuser Timber Company

At the time of this photo in 1941, Weyerhaeuser Klamath Falls employed approximately 1,200 men and produced 200 million feet of wood products each year. Weyerhaeuser experienced a …

Grand Ronde Restoration Hearing

Kathryn, Karen, and Frank Harrison, seated in the front row, testify for Congressional restoration of the Grand Ronde tribe. Elizabeth Furse, an Indian-rights advocate who later became a …