Acquiring Reservation Land

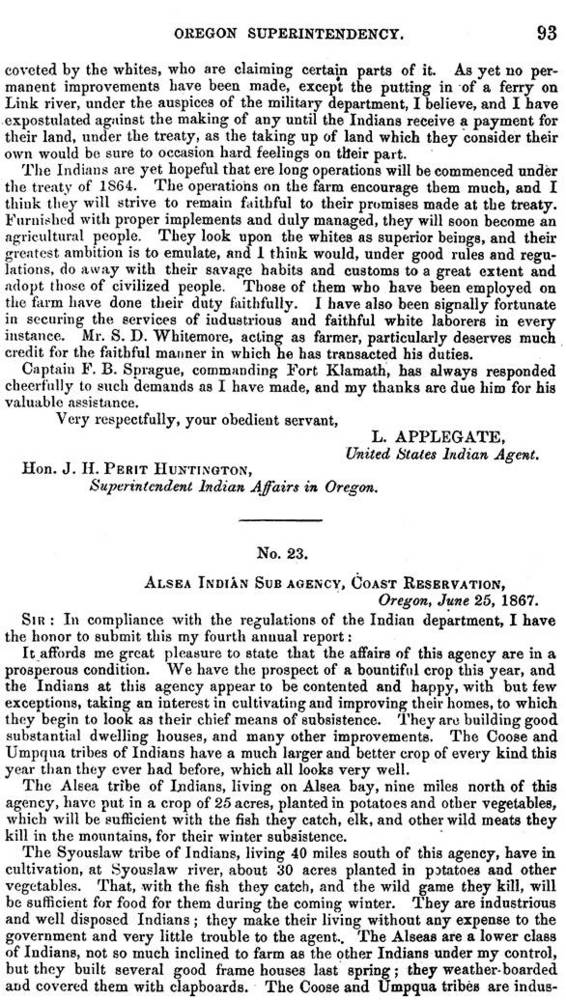

G. W. Collins' June 1867 report on the Alsea Sub-Agency G. W. Collins' June 1867 report on the Alsea Sub-Agency

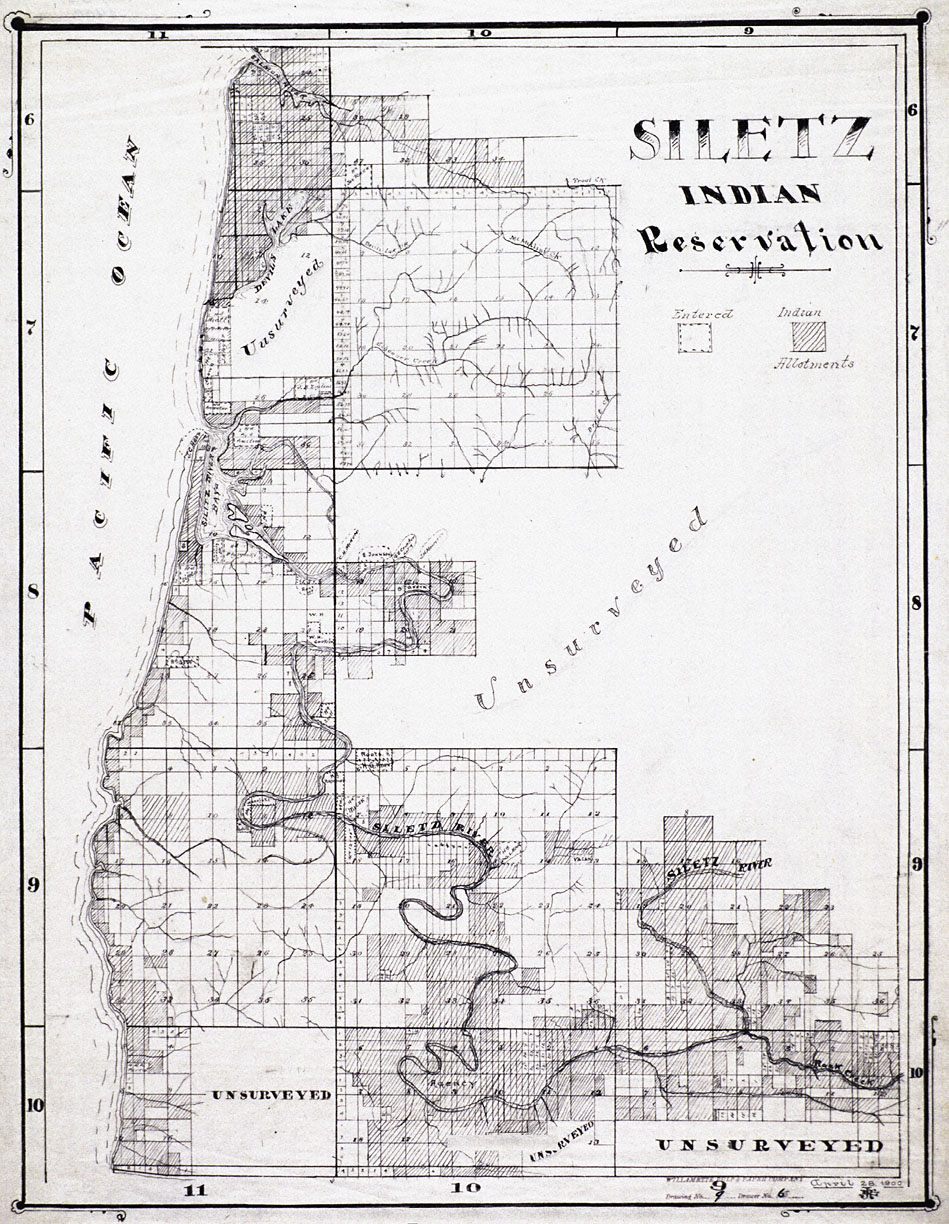

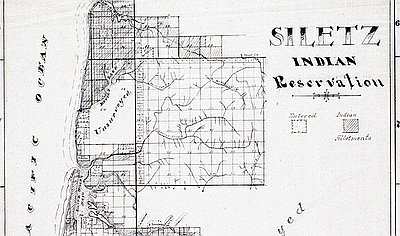

Some of the coast’s most remote and marginal land had been set aside for relocating people who had been defeated in the Rogue Wars and evicted from their homelands along the Rogue, Coquille, Coos, Umpqua, and Siuslaw Rivers. The Coast Indian Reservation (later called the Siletz Reservation), created in 1855, encompassed the entire west side of the central Coast Range, covering more than a million acres from Cape Lookout to the mouth of the Siltcoos River. The Grand Ronde Reservation was established two years later, on the eastern border of the Coast Reservation.

On the reservations, people lived bleak lives in unfamiliar surroundings. In 1858, Indian agent R.B. Metcalfe wrote of the lamentable situation on the Coast Reservation:

The country assigned to these people is poorly adapted to stock raising, there being little or no grass, except on the small prairies, which will be required for cultivation, and the wild game, which was tolerably abundant last year, have all been driven back to the high mountains. As the spring salmon do not run up any of these streams, it leaves us entirely destitute of food during the spring and summer, except as has been provided by the government.

It was not long before pressure to develop land on Yaquina Bay prompted calls from white settlers to acquire some of the reservation land. In January 1852, the schooner Juliet landed at Yaquina Bay in a storm and was marooned for two months. During his enforced sojourn in the area, the captain learned that the bay was full of oysters, a delicacy favored by San Francisco society. In 1863, two oyster companies began operation on the bay.

There was one problem: the bay was part of the Coast Reservation and belonged to the Indians. On their behalf, the federal Indian agent charged a fee of fifteen cents for each bushel of oysters harvested. One of the two companies paid the fee, while the other sued, and lost. A third entrepreneur, whose warehouse on Elk Creek had been torn down by soldiers, took the fight to Washington, D.C. He gained a ruling that the Indian agent had no authority to interfere with his commercial aims.

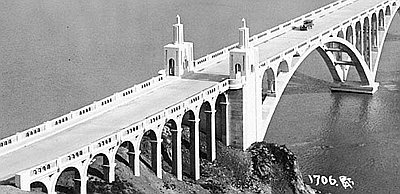

Yaquina Bay also showed promise as a deep-water harbor. By 1864, settlers in the Willamette Valley had begun building a wagon road from Corvallis to the bay, linking the interior with a potential seaport, the town of Newport. In December 1865, President Andrew Johnson signed an executive order excising a twenty-mile-long strip of land, including Yaquina Bay, from the center of the reservation and designating the remaining land as two smaller reservations, the Siletz Agency and the Alsea Subagency.

In 1875, at the behest of Oregon senator John Mitchell, Congress authorized opening the entire Alsea Subagency to white settlement. The subagency was closed, ostensibly as a money-saving measure, and the Siletz Agency was reduced. Over the next few years, the Indians in western Oregon were concentrated on the remnants of the Coast Reservation and on the Grand Ronde Reservation.

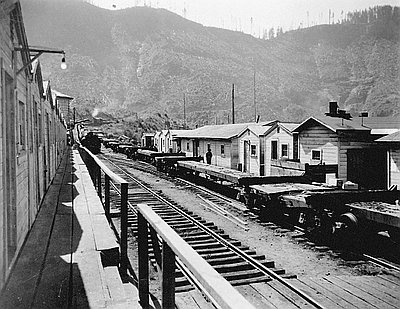

Congress granted railroad rights-of-way through both reservations in 1888, 1890, and 1894. In the 1880s and 1890s, the Dawes Severalty Act of 1887 and other laws pressured Indians to cede most of their collectively held reservation lands and accept individual land allotments. In 1892, when the Siletz lands were allotted, the Siletz Agency contained 225,280 acres; two years later, it contained 46,000 acres.

Those who had been evicted from the Alsea lands when they were opened for settlement in 1875 were offered allotments of public-domain land in Lane, Coos, Curry, and Douglas Counties. They included members of coastal tribes such as the Clatsop, Tillamook, Coos, Lower Umpqua, and Siuslaw, some of whom had returned to their traditional homelands rather than move to the Siletz Reservation.

Settlers and entrepreneurs took advantage of the Indians’ unfamiliarity with the law to take even more of their land. According to historian Stephen Dow Beckham, “The obligations of paying taxes or the allurement of selling the timbered lands to loggers or sawmill owners led over and over again to these Indians’ losing their properties.”

In 1925, the Siletz Agency offices were closed and its administrative duties transferred to the Chemawa Indian School near Salem. Both the Grand Ronde and Siletz Agencies were jointly administered through the School, and later through the Portland Area Bureau of Indian Affairs office. Many Indians continued to live on the reservation lands until 1956, when much of the land was sold and granted to the town of Siletz under the Western Oregon Termination Act (PL 588). During a half-century of reservation life, the Indian population dropped from more than two thousand to fewer than five hundred. In 1977, the Siletz Restoration Act was enacted, restoring the tribal government; in 1980, a portion of the reservation land was returned to the Siletz Tribe.

© Gail Wells, 2006. Updated and revised by OHP staff, 2014.