The Coastal Landscape

The Oregon Coast is a sliver of land between the mountains and the sea, almost three hundred miles long and an average of about fifty miles wide, measured from the high-tide mark to the crest of the Coast Range. The landscape feels rough and unfinished, perhaps because its geological story is still being told. The Pacific Northwest is one of the most geologically active regions on earth, with earthquakes, volcanoes, and young mountains still shaping the land. The roughness is palpable in the shape of the mountains, relatively low but steep, rugged, and dissected with river canyons. The coastal area falls into two physiographic regions: the Oregon Coast Range, stretching between the Columbia and Coquille rivers, and the Klamath Mountains, south from the town of Bandon to the California state line.

The coast is legendary for its rain, which is interrupted in the summer by three months of relatively dry weather. Moisture is brought inshore by Pacific storms, softer mists and fogs drift in, and coastal rivers carry water from the mountains to the sea in an endless cycle. With the exception of the more leisurely Columbia, the rivers race down their conifer-studded canyons before slowing into lower-lying channels lined with cottonwoods, alders, willows, and deciduous shrubs. As they near the ocean, the rivers widen and wend their way through grassy river bottoms. Some flow into broad estuaries, while others empty directly into the sea.

The Columbia, largest by far of the coastal rivers, flows into the ocean at Astoria on the Oregon-Washington state line. About thirty miles to the south, the Tillamook and four other rivers empty into the sock-shaped Tillamook estuary. It is about forty miles to the next major river to the south, the Siletz, at Gleneden Beach. Twenty miles farther, the Yaquina River forms a good-sized estuary at Newport. Another twenty miles south, the Alsea empties into a smaller bay at Waldport. Then the coastline rises to a series of headlands, beginning with Cape Perpetua, that juts into the ocean south of Yachats.

From Cape Perpetua to Florence, the coastline traverses a series of east-west ridges drained by small creeks. The Siuslaw River enters Florence’s small estuary, and the Smith and Umpqua Rivers form a larger estuary at Reedsport before bisecting the forty-mile-long strip of sand dunes that stretches from Florence to North Bend.

The largest estuary south of the Columbia is Coos Bay, formed by the Coos River and its several inlets and sloughs. South of the mouth of the Coquille River at Bandon, the Klamath Mountains begin to press up against the coastline and the rivers flow straight into the ocean. The Coquille enters the Pacific in at Bandon, and the Sixes and Elk Rivers enter at Port Orford. In between is Cape Blanco, the westernmost point in Oregon. Along the stretch of coastline where the Rogue River enters the Pacific at Gold Beach and the Chetco enters at Brookings, the climate is warmer, the harbors are smaller, and the communities are more isolated than is the case farther north.

The Oregon Coast is a landscape of mild temperatures, lush vegetation, and abundant terrestrial and sea life. With the exception of the Columbia, coastal river valleys are narrow, and there is little arable land in the mountainous and forested landscape. While farming has been important in the Euro-American settlement of the coast, it has nearly always played a secondary role to timber, the area’s major economic engine.

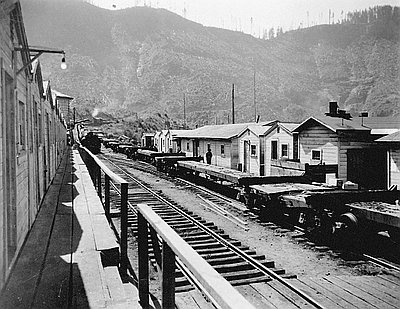

A study of the interplay of natural history and human actions along the Oregon Coast since about 1700 reveals certain broad themes. The first is isolation, owing primarily to physiographic realities. As the Pacific Northwest lagged behind the rest of the United States in economic development, the coastal strip lagged behind the rest of the region. For most of the settlement period, coastal communities have been isolated from one another, giving each a more distinct local character than settlements inland.

The second theme is a strong federal presence, manifested in policies affecting Native Americans and tribal nations, transportation structures (railroads, highways, port facilities), wartime wage and price controls, modern-day recreational opportunities, and laws governing the timber industry and land disposal.

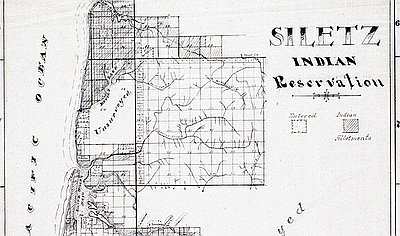

The third theme is the tension and inequities that have existed in Indian-white relations since the earliest contact. From the time Euro-Americans first sailed along the coast or set foot in the Northwest, their general treatment of Native peoples was harsh, driven by conquest, extermination, or forcible assimilation. It was not until the 1970s that coastal Indian people gained a measure of restored sovereignty.

Fourth, the Pacific Northwest has served as a hinterland to the nation and the world, with the coast seen as a hinterland to the larger region and the Pacific Rim. As a result, economy, culture, and regional character of the Oregon Coast have been strongly shaped by its role as a provider of natural resources to the world.

Finally, the people of the Oregon Coast exemplify complicated cultural attitudes. They have tended to think of themselves as possessing an independent pioneer spirit (a persistent theme in the cultural mythology of the Pacific Northwest), but it is a perception that is in contrast to the reality of the region’s economic dependence on the outside world. There is a universally declared love of nature, which is not surprising given that the coast has some of the most spectacular scenery and natural features in the world. Yet, the industries that have enabled residents to settle and stay and make their living are lumbering, fishing, mining, and farming, activities that are hard on the natural environment.

According to the 2010 census, the counties that touch the coast—Clatsop, Tillamook, Lincoln, Lane, Douglas, Coos, and Curry—make up 16 percent of Oregon population. Hispanics form the largest growing ethnic community on the coast, with the largest percentage in Tillamook County (9.4 percent); Latinos/Latinas constitute between 4.9 and 8.2 percent in the remaining counties. The coastal counties have an average Native American population of 2.1 percent. Lincoln County, the home of the Siletz Reservation, has the largest Native community among coastal counties, at 3.9 percent. Coos County has the second largest percentage at 2.8, with portions of the Coos, Lower Umpqua, and Siuslaw Reservation and the Coquille Reservation within its borders. Lane County has the most significant Asian American population in the region, measuring 3.9 percent; the remaining counties include between 0.8 and 1.3 percent Asian Americans. Lane County also includes the highest percent of African Americans in the area, 1.1 percent. The other counties include less than 1 percent African Americans.

Natural resource industries have produced an economy characterized by two emblematic and dichotomous figures: blue-collar workers or manual laborers and the entrepreneurs who put those men and women to work in the woods, the mills, the canneries, and the dairy farms. The promise of becoming a timber or mining tycoon, striking it rich through grit and luck, seduced many who immigrated to the coast in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. The idea of Oregon as a land of promise often has collided with an unpromising economic reality.

© Gail Wells, 2006. Updated and revised by OHP staff, 2014.

Sections

Related Historical Records

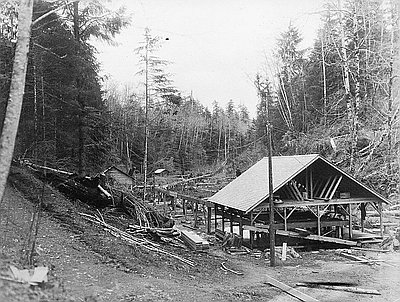

Bandon Hatchery, Coos County

As early as 1902, the Oregon State Fish Commission established an experimental hatchery station on the Coquille River, near Bandon on the southern Oregon Coast. In 1910, the …

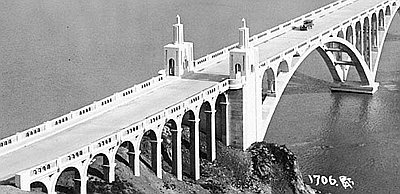

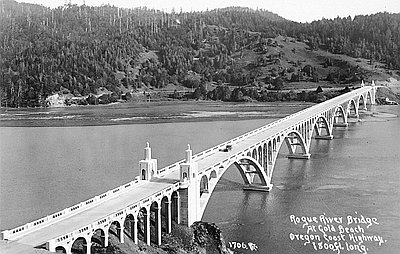

Rogue River Bridge, Gold Beach

The Isaac Lee Patterson Bridge across the Rogue River on Highway 101 at Gold Beach is depicted above at the time of its completion in 1931; it was …

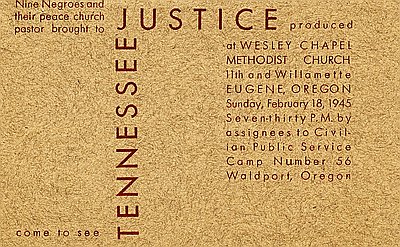

Leaflet, Tennessee Justice

This leaflet was produced by members of the Civilian Public Service Camp #56 at Waldport. It is an advertisement for a play that members of the camp performed …