Trade

As the eighteenth century came to a close, people on the Oregon Coast not only regularly traded with nearby villages but they also had occasion to trade with voyagers in seagoing canoes from the north. For centuries, people had traveled to upriver fishing places and to berrying grounds in the nearby mountains. On the northern coast, the Tillamook people knew the trail that traversed the headlands, and they were familiar with those who lived to the north and the south. Perhaps as early as the 1640s, some villagers were also aware of sailing ships that touched landfall along the coast. Europe’s interest in the North Pacific quickened in the last quarter of the eighteenth century, as Spanish, British, French, Russian, and eventually ships from the United States came into increasing contact with Native people in coastal estuaries.

The ships arriving on the Northwest Coast entered long-established places of trade and commerce. The voyages, which represented an expanding imperial geography of Old World and New World powers in search of national aggrandizement and markets, are usually described as “discovery” in the historical literature. Those voyages, in fact, were in the process of gathering information for British, European, and American communities of interest that which was unknown to them. While that distant imperial contact with the peoples on the Northwest Coast ultimately introduced killing diseases to the region, the immediate result was to increase trade prospects for local people. The expanding trade networks also brought Native people within the embrace of the global market.

While the long-term consequences of maritime voyages were similar, there were significant differences among European scientific exploration and trading ships. The exploratory travels of British naval captains James Cook and George Vancouver and the trading voyages of American ship captain Robert Gray illustrate some of those differences.

Cook and Vancouver produced an extensive and detailed cartography of the North Pacific, especially the coastal region from present-day Alaska to northern California. In addition, their scientific explorations gave the world new information on Native peoples, flora and fauna, and potential commercial resources, especially pelagic furs. Gray’s purpose was focused on trade, and he pursued that activity with Native groups, with land and pelagic furs as his principal focus. Traders like Gray provoked conflict with local people more often than explorers did.

Cook’s third voyage was to the Northwest Coast, and he wintered in Nootka Sound on the west coast of Vancouver Island. He failed to locate the elusive Northwest Passage or the entrance to the Columbia River, and he also failed to recognize that Nootka Sound was located on a large island and not on the North American mainland. Conventional historical narratives have treated Cook’s stay at Nootka Sound as a principal building block of Pacific Northwest history. Such approaches distort the region’s history because they ignore native people and condition readers to privilege such “heroic” stories.

Capt. George Vancouver, who sailed with Cook on his second and third voyages, sailed into the North Pacific in 1792 on a cartographic surveying mission for the British government. His instructions were to chart Pacific Northwestern waters and to provide detailed descriptions of “every principal entity whose position is either wholly or even thro’ Accident only partially and incompletely determined.” He was to produce an authoritative and accurate geography, with special attention to the Northwest Passage.

Vancouver mapped the Pacific Coast from Cape Mendocino north to Vancouver Island, including Puget Sound and the island he named for himself. Vancouver’s crew carried out its work with detailed scientific precision and in the end concluded that the Northwest Passage did not exist. The survey acknowledged only a few of the place-names given to the landscape by earlier Spanish explorers and made only passing mention of a few Native villages. Keeping faith with the British Admiralty’s instructions, Vancouver gave “significant and Characteristic Names” to major Northwest landmarks, including Bellingham Bay, Whidbey and Vashon Islands, and Mt. Hood and Mt. Rainier. The captain, geographer Daniel Clayton wrote, “emphasized his—and Britain’s—presence.”

Robert Gray’s exploration of Pacific Northwest waters is another story. A privateer captain during the American Revolution, Gray was without a ship and looking for work in the mid 1780s when news arrived in Boston of James Cook’s report that sea otter pelts from the Northwest Coast could be sold for great profits in China. With the support of New England maritime investors, Gray set sail in 1787 for the Northwest, where he spent the winter trading for the valuable pelts. He sold the furs in Macao and returned to Boston in 1790. Within a month, he was freshly outfitted with trade goods and was once again bound for the Northwest Coast.

After wintering at Adventure Cove in Clayoquot Sound on the west coast of Vancouver Island, Gray went in search of sea otters. On the evening of May 10, 1792, his ship, the Columbia Rediviva,cleared the entrance to what is today Gray’s Harbor on the Washington Coast and continued south toward a bay where Gray had noted a strong outflow a week earlier. On the following morning, the ship crossed the bar into the river that Gray would name the Columbia in honor of his ship. He made no claims of possession but carried on a brisk trade with local people, leaving on May 20 with 300 beaver and 150 sea otter pelts.

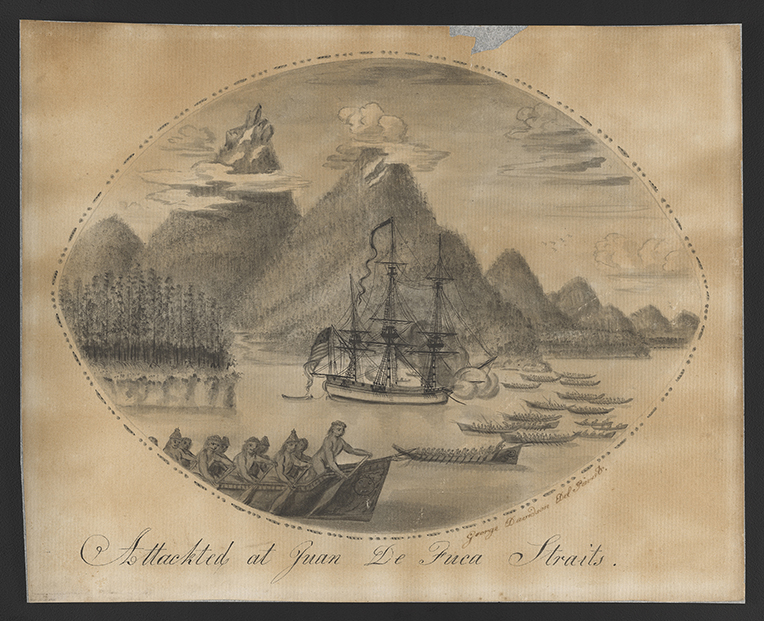

In truth, the Bostonian was little interested in exploration and geography other than the prospect that such knowledge might enhance his investments. Historian Dorothy Johansen characterized Gray as “a hard man, strictly attention to ‘two-penny objects’ of his business—to get sea otter skins and invest them in China goods.” The captain’s dealings with Native people, especially during his second voyage, were contentious, and on several occasions—with only the slightest provocation—he ordered his crew to destroy villages and blow Indian canoes out of the water. Before leaving his winter quarters in Clayoquot Sound in March 1792, for example, Gray directed his crew to destroy a village with some two hundred dwellings. John Boit, a mate aboard the ship, confided to his journal: “am grieved to think Captain Gray should let his passions go so far.” Three days before the Columbia made its historic crossing of the Columbia bar, Gray’s ship directed musket and cannon fire on several canoes, sinking one large craft and killing all its occupants. In May, near Clayoquot, they destroyed another canoe, killing everyone on board.

By the close of the eighteenth century, the Northwest Coast had become a place with an emerging global economy. In the coastal areas and elsewhere, Native people and westerners interacted, sought power and influence, and carried on exchanges of goods and services. The maritime fur trade involved negotiations between equals, with each party contesting for advantage in the exchange relationship. To Native people, there were fundamental differences between the maritime and land-based fur traders and the settlers who followed. The traders needed Native people to provide them with furs and local knowledge, to serve as a labor force in transporting furs, and to act as guides through unfamiliar country. In distant places, however, imperials nations—especially England and the United States—were beginning to joust for advantage in the Northwest.

Centered primarily on sea otters, the maritime fur trade from 1785 to 1815 underscores the extractive nature of the market economy that developed in the Pacific Northwest during the nineteenth century. It was not what we think of as classic market exchange, because Native people took part in the trade for cultural reasons. Although they provided the labor and in many respects controlled the terms of the trade, trouble lay ahead. When fur-bearing animals became scarce, those who had come to rely on the trade for their livelihoods were left with few alternatives. Then there was the disease factor. As ships from Europe and the United States came into increasing contact with the Northwest Coast, they left in their wake Old World contagions, such as smallpox and measles, that were disastrous for Native people.

The coastal and interior fur trade provided a way for European businessmen to accumulate capital in cities such as London, Montreal, Boston, and New York, and the sea otter trade launched several New England fortunes. The trade also resulted in shifting imperial claims to the region, with Spain controlling only remnants of its empire south of the 42nd parallel. The Russians, who began establishing outposts along the North Pacific coast in the 1740s, were increasingly confined to Alaska. American and British interests became dominant across much of the Columbia Basin and beyond.

Between the turn of the nineteenth century and the settlement of the Oregon boundary dispute in 1846, however, those imperial claims were largely empty boasts. Native peoples from coastal villages to the interior Plateau were still autonomous groups that enjoyed freedom of movement and association, and many of them were only peripherally involved in the developing market economy. With the election of Thomas Jefferson to the presidency of the United States in 1800, however, forces were set in motion that would eventually marginalize Native people in their own homelands.

© William G. Robbins, 2002. Updated and revised by OE Staff, 2014.

Sections

Related Historical Records

Captain Clark at Tillamook Head, 1806

In the journal entry reproduced here, Captain William Clark offers a detailed description of the northern Oregon coast as he encountered it on January 8, 1806. Standing at …

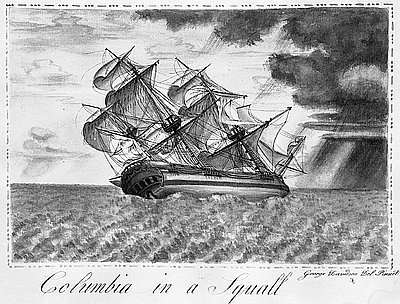

Columbia in a Squall

This painting shows the Columbia Rediviva heeling to the side as it approaches a squall. It was painted in 1793 by amateur artist George Davidson, the Columbia’s painter. …

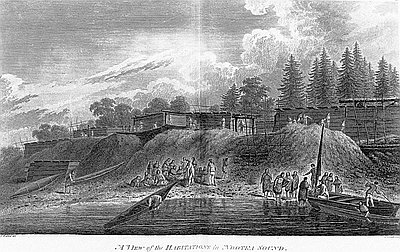

View of the Habitations in Nootka Sound

This engraving represents men from Captain James Cook’s third voyage to the Pacific Ocean meeting with Native Americans on the beach below what is probably Yuquot, the summer …