Jefferson's Instructions

Months before his message to Congress, the president had chosen Meriwether Lewisto lead the western expedition. A fellow Virginian and son of a plantation owner near Monticello, Lewis was a captain in the army with extensive knowledge of military discipline, experience on the western frontier, and as Jefferson put it “habituated to the woods, & familiar with Indian manners & character.” Lewis had served Jefferson since early in 1801, when the president had selected him as his private secretary to aid in the president’s plan to reduce the size of the regular army. Lewis perused Jefferson’s library and discussed the western regions with him, especially after the president decided to launch the expedition. By late June 1803, Jefferson had formulated a letter of instruction that outlined an ambitious exploration agenda. In the meantime, Lewis had enlisted William Clark, experienced frontier army soldier and younger brother of Revolutionary War hero George Rogers Clark, to join him as co-captain of the Corps of Discovery.

In his letter of instructions to Meriwether Lewis, national expansion and economic development dominated Jefferson’s thinking. He was explicit: “The point of your mission is to explore the Missouri river, & such principal stream of it, as, by it’s course and communication with the waters of the Pacific ocean, whether the Columbia, Oregan, Colorado or any other river may offer the most direct & practicable water communication across this continent for the purposes of commerce.”

Jefferson directed the captains to proceed up the Missouri River, note the tributaries, establish accurate maps of the region, and identify important locations for economic activity. He instructed Lewis and Clark to record information on an expansive list of scientific subjects, including flora, fauna, climate, mineral locations, and soil types that might support various kinds of agriculture. He instructed them further to note “interesting points of the portage between the heads of the Missouri, & of the water offering the best communication with the Pacific ocean [with] . . . observations . . . taken with great pains & accuracy, to be entered distinctly & intelligibly for others as well as yourself.”

Accurately plotting the landscape for posterity and future use figured prominently in the explorers’ work. Cartography and especially the accurate notations of longitude and latitude were an important part of an Enlightenment-informed scientific inventory of the region. Drawing maps of the new region had significance because they fulfilled Jefferson’s long-held desire for knowledge about the West, they established more secure claims to territory, and they were precursors of detailed surveys that would lead to land sales and settlement. In addition, the captains laid down names on their maps, names that reflected American possession of the territory, thereby extending a form of control over nature and places in the American West.

Jefferson also included detailed instructions on how the Corps should engage Native peoples. Lewisand Clark were to “treat them in the most friendly & conciliatory manner which their own conduct will admit.” The goals were peace and friendship, watchwords emblazoned on peace medals the captains would bestow on selected Indian leaders they encountered. Peace and friendship, in Jefferson’s mind, were prerequisites for trade relationships, a principal symbol of government policy toward Missouri River Indians. Rather than acquire Indian lands as he had from tribes east of the Mississippi, Jefferson wanted to create an Indian territory in the recently purchased territory that would presage inclusion of western Indians into an expanded American republic. It was an expansive imperial agenda.

The president believed that developing strong trade and political alliances with Indian nations would lead seamlessly to converting tribal cultures to agricultural communities, as he later told tribal leaders in 1808: “When once you have property, you will want laws and magistrates to protect your property and persons [and]. . . . You will find that our laws are good for this purpose.’

With these larger purposes in mind, the list of instructions detailed query upon query about Native cultures. Jefferson directed the captains to quiz Indians about the extent of their homelands, their relations with other tribes, their language, traditions, moral codes, and much more. In addition to being political representatives of their nation, the Expedition leaders would also be Jefferson's ethnographers.

Jefferson had handed Lewis and Clark a daunting list of tasks that required scientific and technical abilities, talent in diplomacy, political sagacity, backwoods adeptness, military adroitness, and literary and cartographic competence. The list of goals also posed challenges, a kind of test of Jefferson’s whole idea. Could a catalog of the West be collected in an expedition that embraced so many risks and spanned such a distance? Could Lewis and Clark find a route to the Pacific that had commercial value? Could the captains successfully engage Native peoples and construct economic and political alliances with them? Jefferson had laid out the challenges and understood the risks. At the end of his letter of instructions, the president requested:

To provide, on the accident of your death, against anarchy, dispersion, & the consequent danger to your party, and total failure of the enterprize, you are hereby authorised, by any instrument signed & written in your own hand, to name the person among them who shall succeed to the command on your decease.

The Corps of Discovery—an idea nurtured by Thomas Jefferson for more than two decades, infused with his dedication to Enlightenment science, and powered by his vision for western America—had its instructions, its mission, and its historical burden.

© William L. Lang, 2004. Updated and revised by OHP staff, 2014.

Sections

Related Historical Records

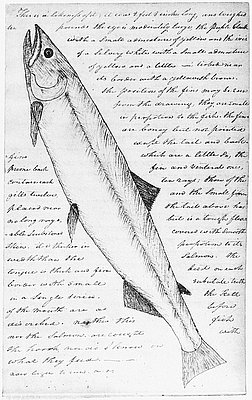

Clark's Drawing of White Salmon Trout

This is a copy of a sketch made by William Clark in February 1806, while Expedition members were at Fort Clatsop near the mouth of the Columbia River. …

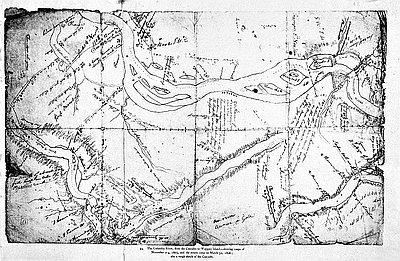

Columbia River from the Cascades to Wappato

This map, sketched by explorer Captain William Clark in early November 1805, shows the Columbia River between the Cascade Rapids and Sauvie Island — which Clark called “Wappato Island” …

Principal Watercourses West of the Rockies

The document reproduced here is Captain William Clark’s copy of a map sketched by two Nez Perce Indians in May 1806. It shows the principal river systems west …