After the Expedition

The Lewis and Clark story did not end with the return of the expeditionary force. What happened to the Expedition’s records, materials, and members after the journey reflect significantly on the exploration epic. Jefferson had taken political risks, first when he had asked Congress to authorize the Expedition and second when he approved the purchase of Louisiana. One political opponent criticized the purchase as “a great waste, a wilderness unpeopled with any beings except wolves and wandering Indians.” Others questioned how the nation could afford to administer such an extensive region.

Jefferson understood that how his administration handled the new territory and what the Lewis and Clark Expedition revealed about its potential would either quiet his critics or give them political ammunition. Jefferson committed little political capital in his official reference to the Expedition, saying it “had all the success which could have been expected” and adding that Lewis and Clark “by this arduous service deserved well of their country.”

Jefferson rewarded the captains by appointing Lewis governor of Upper Louisiana Territory and making Clark chief Indian agent and brigadier general of the Louisiana territorial militia. Both would settle into their roles in St. Louis in 1808. For reasons that are unclear, however, Lewis did not fulfill his main post-Expedition task: writing a thorough account of the journey for publication.

Beset by questions raised about his handling of territorial expenditures and his writing dalliance, Lewis set out to Washington, D.C., in October 1809 to defend his work and reputation. According to one report, he seemed “at times deranged in mind,” and whatever bedeviled him drove him to end his life at a roadside house in Tennessee. “I fear O! I fear the waight of his mind has over come him,” Clark wrote to his brother on hearing the news. Jefferson later characterized Lewis as “much afflicted & habitually so with hypcondria.” Losing a friend who was also a confederate in scientific investigations must have grieved Jefferson, but it is also true that the president had grown tired of waiting for Lewis’s full account of the Expedition, especially publication of his scientific findings.

The history of the journals themselves is anguished. The first rendition of the exploration came out in 1807, a version of events written up by a publisher from journals kept by Patrick Gass. The first official and more completed version did not see print until 1814. A young Philadelphia lawyer and writer, Nicholas Biddle, took on the task in 1810 and worked steadily, often in consultation with Clark, to produce The History of the Expedition Under the Commands of Captain Lewis and Clark. Although it stood as the official edition, it did not include important materials, including Clark’s field notes, journals by other Corps members, the complete maps, and the herbarium. It took more than 150 years to collect the scattered pieces that has become the most complete edition. Between 1979 and 2001, the University of Nebraska Press published thirteen volumes of The Journals of the Lewis and Clark Expedition, under the editorship of Gary Moulton, to date the last word in Lewis and Clark literature.

© William L. Lang, 2004. Updated and revised by OHP staff, 2014.

Sections

Related Historical Records

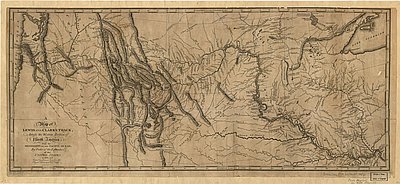

Map of Lewis and Clark's Track

This map, titled A Map of Lewis and Clark's Track across the Western Portion of North America from the Mississippi to the Pacific Ocean, published in 1814, is …

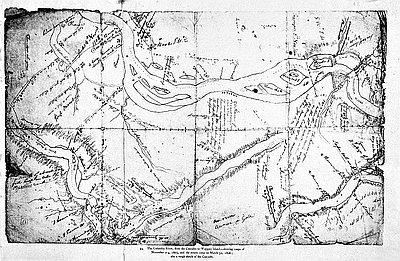

Columbia River from the Cascades to Wappato

This map, sketched by explorer Captain William Clark in early November 1805, shows the Columbia River between the Cascade Rapids and Sauvie Island — which Clark called “Wappato Island” …

Death of Meriwether Lewis

The death of Meriwether Lewis in the fall of 1809 has long been a subject shrouded in mystery and controversy. This much we know: on September 4, 1809, …