America's Pacific Vision

For sparsely settled Oregon, the result of new railroads, new irrigation canals, new farms, and new logging techniques was a dramatic 63 percent rise in population between 1900 and 1910—from 413,000 to 673,000. Only the 40 percent increase during the World War II decade would come close to such a rate of growth in the state. By comparison, Oregonians in the 1990s felt overwhelmed by a growth of 20 percent.

It was no surprise that Portland more than doubled in size, from 90,000 to 207,000. The city was far in front of its rivals and pulling away. Next in line were Astoria, Baker City, Pendleton, Salem, and The Dalles, but none had more than 10,000 residents. Nevertheless, Oregon’s population in the early twentieth century was more evenly balanced by region than before or since. About 25 percent of Oregonians at the time of the Exposition lived in Multnomah County, 25 percent lived east of Cascades as they exploited the dry frontier (only 12 percent of Oregonians would live on the east side in 2000), 30 percent in rest of the Willamette Valley, and 20 percent in southern Oregon and along the coast.

On the opening day of the Exposition, Vice President Charles Fairbanks sounded a theme for Oregon’s—and the nation’s—new century. “The future has much in store for you,” he intoned. “Yonder is Hawai’i, acquired for strategic purposes and demanded in the interest of expanding commerce. Lying in the waters of the Orient are the Philippines which fell to us by the inexorable logic of a humane and righteous war. We must not underrate the commercial opportunities which invite us to the ‘Orient.’”

Fairbanks’s speech harkened back to Thomas Jefferson’s vision of an expanding realm of trade and liberty that would span the continent and the Pacific. William Clark and Meriwether Lewis,after all, trekked up the Missouri River and down the Columbia to seek out a good trade route, and American ships and fur traders were already linking the Northwest Coast, Hawai’i, and China in a lucrative trade. Thomas Hart Benton, the Missouri senator who gave his name to an Oregon county, proclaimed a vision of continental expansion in the 1820s and 1830s. Even the war with Mexico in 1845 was motivated in part by the desire to gain control of California harbors.

The Pacific vision receded in mid-century as the nation struggled with sectional conflict over slavery expansion, fought a civil war, and struggled to reconstruct a continental republic. A new Pacific imperialism arrived with the Republican administrations of William McKinley (1897-1901) and Theodore Roosevelt (1901-1908). The U.S. annexed Hawai’i, divided Samoa with Germany, and took control of Guam and the Philippines after the Spanish-American War of 1898. In 1903 the U.S. established what was effectively a protectorate over the new nation of Panama, which it encouraged to split off from Colombia, and acquired control of a ten-mile strip across Panama for a canal.

Work on the Panama Canal kindled interest in Pacific trade all along the West Coast. Businessmen noted that economical routes around the Pacific skim the west coast of the Americas and the east coast of Asia. Cities from San Diego to Seattle anticipated an explosion of trade when the Panama Canal tied the Pacific and Atlantic worlds. Journalists caught Panama Canal fever and penned stories about “The Coming Supremacy of the Pacific” and “The Momentous Struggle for Mastery of the Pacific.”

The Los Angeles Chamber of Commerce sponsored “Los Angeles: A Maritime City” (1912), a pamphlet that pointed out the easy course from the harbor at San Pedro to Japan. Also in California, historian and history publisher Hubert Howe Bancroft had recently combined a boosterish inventory of western resources with the ancient trope of the westward course of empire in The New Pacific. The twentieth century, he proclaimed, would be the century of the new Pacific, with North Americans shouldering aside tired Europeans and the wealth of the Pacific surpassing that of the Atlantic. The vision was one of classic liberalism, with free trade in goods and ideas lifting the strongest individuals and nations to success.

We have no longer a virgin continent to develop; pioneer work in the United States is done, and now we must take a plunge into the sea. Here we find an area, an amphitheatre of water, upon and around which American enterprise and industry, great as it is and greatly to be increased, will find occupation for the full term of the twentieth century, and for many centuries thereafter. The Pacific, its shores and islands, must now take the place of the great west, its plains and mountains, as an outlet for pent-up industry.

The Pacific vision resonated with Oregon’s leaders. Oregon had grown in the nineteenth century largely by feeding and housing California. San Franciscans and ’49ers had provided the original market for wheat and lumber in the 1850s, and Californians continued to be the state’s biggest customers. By 1905, however, Oregonians were casting their eyes across the ocean. The perfect complement to the resources of the Northwest, said Oregonians, was the huge potential market of the Pacific Rim. Exposition president H.W. Goode claimed that the fair “will demonstrate to the commercial world . . . the actual inception of the era of new trade relations with the teeming millions of Asiatic countries.”

In hearings before the House Committee on Industrial Arts and Expositions in 1904, Jefferson Myers of the state commission went straight to the point. “If all the wheat raised west of the Mississippi River were ground into flour for the Chinese trade,” he told the panel of congressmen, “the consumption per Chinaman would not exceed one pancake per month.” Harvey Scott, editor of the Oregonian, asserted that the future trade of the Pacific would rival that of the Atlantic and orated in the practiced generalities of a journalistic booster. “That future is begun already,” he concluded. “It is manifest, it presses, and it remains for us of America to seize it, to bear our part of it. We propose our exposition both as an incident and as an agent of this coming greatness.” He commented later that it was the Pacific idea that sold Congress on federal participation in the Exposition.

© Carl Abbott, 2004. Updated and revised by OHP staff, 2014.

Sections

Related Historical Records

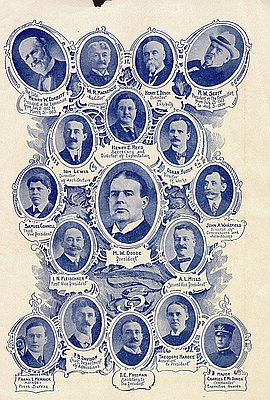

Exposition Company Leaders

This image, showing the directors and officers of the 1905 Lewis and Clark Exposition, is from the fair’s “Portland Day” program. The officers were mostly local businessmen, who …

Second Oregon Crosses River in Philippines, 1899

This photograph shows Company I of the Second Oregon Volunteer Infantry Regiment crossing a river (identified as either the Quinqua or the Norzagaray) in the Philippines during the …