Ocean in View

Reaching the Pacific Coast nearly finished off the Corps. At no other time during the Expedition were physical conditions so threatening as they were in the Columbia River estuary, where there were lashing rains, strong winds that whipped up a furious chop on the river, and very few campsites. The Columbia held the Corps hostage for several days in November at Point Ellice, just a few miles from the ocean. The fierce conditions had driven the Corps up against the northern river bank, where falling stones, driftwood, and high winds put them “at the mercy of the waves . . . our Selves and party Scattered on floating logs and Such dry Spots as can be found on the hill Sides, and Crivices of the rocks.” Clark wrote despondently of the situation:

The rainey weather Continued without a longer intermition than 2 hours at a time from the 5th in the morng. untill the 16th is eleven days rain, and the most disagreeable time I have experienced Confined on a tempiest Coast wet, where I can neither get out to hunt, return to a better Situation, or proceed on: in this Situation have we been for Six days past.

They persevered and made their way around Baker Bay and across the Long Beach peninsula to the coast on November 19, where Expedition members tramped the coastline and Clark carved his name “on a Small pine, the Day of the month & year, &c.”

Achieving their goal had brought elation to the Corps, even though the weather continued unpleasant and discouraged them from staying at the coast for the winter. The captains, as Joseph Whitehouse recorded, “had the whole party assembled in order to consult which place would be the best, for us to take up our Winter Quarters at.” Two objectives guided their choice. First, they needed salt and plentiful game for sustenance. Second, and perhaps as important, the captains held out for visitation by one of the maritime traders that frequented the Columbia. A trading ship could bring goods and a means to send collected materials home.

Meeting a trade ship on the coast was important enough for economic and political reasons that the captains queried Indians during the winter about how often traders came, what they traded, how they conducted themselves, and what nations they represented. It became evident that coastal peoples not only bargained assiduously and successfully with maritime traders, but they also formed relationships with specific ship captains and crews. Lewis and Clark soon realized that the people of the coast were discerning and sharp traders. The Clatsop and Chinookan people, Lewis wrote in January 1806, were friendly, but they were as likely to “pilfer” as trade, and they were tough bargainers.

They are great higlers in trade and if they conceive you anxious to purchase will be a whole day bargaining for a handfull of roots; this I should have thought proceeded from their want of knowledge of the comparitive value of articles of merchandize and the fear of being cheated.

Meriwether Lewischose a winter quarters site on a stream that emptied into one of the bays in the Columbia estuary that was seemingly on good elk-hunting grounds and close enough to the seashore to establish a salt-distilling operation. Clark called the place “the most eligable Situation for our purposes of any in its neighbourhood.” In just under four weeks, the Corps built a modest stockade, which featured several attached cabins surrounding a central yard.

The captains operated Fort Clatsopon a different model than Fort Mandan. By their orders, sentinels patrolled the gate and Indians could not remain inside the fort after dusk. The heightened security reflected their need to protect goods and control interaction between Indians and Corps members. Relationships at Fort Clatsop took a much different turn than they had at Fort Mandan.

Lewis and Clark recorded mixed feelings about the Clatsop, Tillamook, and Chinook who lived along the coast, both north and south of the Columbia. In some journal entries, the captains commented on their friendliness, but they also criticized the Clatsops and Tillamooks for stinginess and their reluctance to trade. They considered the Chinooks to be thieving and also reluctant traders.

In trade relations, conditions conspired against Lewis and Clark. They arrived on the lower Columbia with few trade goods left in their store and what they had looked inferior and relatively valueless to Indian traders, who had become accustomed to the quality and variety of goods purveyed by maritime traders. In one instance, Indian traders rejected proffered articles but spied Sacagawea’s beaded belt and managed to make an exchange for it. Establishing any kind of permanent trade relationship seemed beyond the captains’ grasp. They even had difficulty trading for food.

Chinook, Clatsop, and Tillamook physical appearance and behavior drew the most critical appraisals from Lewis and Clark. They had complained about Indian theft throughout their descent of the lower Columbia, but at the coast they added a string of caustic evaluations that focused on body types and social behaviors. Describing all of the coastal peoples, Lewis called them “reather diminutive, and illy shapen; possessing thick broad flat feet, thick ankles, [and] crooked legs.” Clark described Chinook women’s behavior critically, noting that they “are lude and Carry on Sport publickly.” About the men, Lewis commented, that “they do not hold the virtue of their women in high estimation, and will even prostitute their wives and daughters for a fishinghook or a stran of beads.”

The captains misunderstood gender relations, trade practices, and the social structure of coastal groups. The combination of a disagreeable climate, no visiting ships, unsuccessful trade relationships, and too much idleness among the Corps made for an unflattering portrait of the lower Columbia in the captains’ minds.

© William L. Lang, 2004. Updated and revised by OHP staff, 2014.

Sections

Related Historical Records

Tsin-is-tum (Jennie Michel)

Pictured here is Tsin-is-tum, a Clatsop Indian woman known to whites as Jennie Michel. She claimed to be about 100 years old when this photo was taken in …

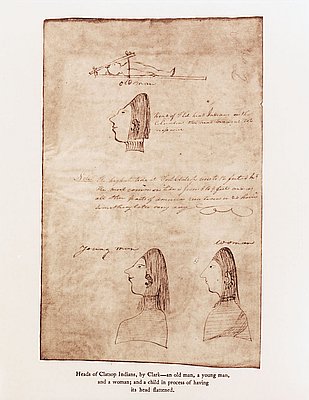

Chinookan Head Flattening

These illustrations from the journal of William Clark depict what many white explorers and fur traders considered to be a peculiar practice among the Chinookan people and other …

Captain Clark at Tillamook Head, 1806

In the journal entry reproduced here, Captain William Clark offers a detailed description of the northern Oregon coast as he encountered it on January 8, 1806. Standing at …