Arrogant "Anthropology" and the Dynamics of Ethnic Change

If Indians by 1905 were strangers in their own land, the Exposition also introduced new peoples to occupy the low spot on the supposed continuum from savagery to civilization. White Americans and Europeans at the turn of the last century were preoccupied with ordering different national and ethnic groups into a hierarchy of superior and inferior peoples. Those doing the rankings always managed to put themselves at the top—“Anglo-Saxon Americans,” Germans, English, French—and then arrayed their inferiors according to standards derived from psychology, anthropology, and economics.

The philosophy of social Darwinism emerged to explain why the powerful groups and nations deserved their power—they had presumably shown their fitness by out-competing their rivals. The standards enlisted social science on behalf of European imperialism in Africa and Asia, German aggression in eastern Europe, and American discrimination against African Americans and Latinos. They similarly justified H.H. Bancroft’s vision of the Pacific as an arena for Darwinian competition: “Here on this ocean all the world will meet, and on equal footing, Americans and Europeans, Asiatics and Africans, white, yellow, and black, looters and looted, the strongest and cunningest to carry off the spoils.”

U.S. control of the Philippines, which had both sophisticated cities and rural backwaters, provided the opportunity to combine showmanship and popular anthropology. The International Anthropological Exhibit Company was organized in St. Louis in 1904 to exhibit Filipino villagersaround the country, including world’s fairs, state fairs, and possibly Coney Island. They would be billed as the most primitive of primitive peoples—near naked savages who ate dogs. If Filipinos were savages, of course, American control of the islands was justified and independence could be put off—regardless of four centuries of Spanish-Filipino culture and Christianity and the fierce war for independence that Filipinos had waged (and lost) after 1898.

Lewis and Clark organizers thought they had agreement for an exhibit of Igorrote, Visayan, and Negrito villages nailed down as part of the Trail. But Secretary of War William Howard Taft had second thoughts about the commercial exploitation of Filipinos, bringing frantic pleas from Henry W. Goode, who wanted the “widely advertised Igorotee (sic) village as ethnological and educative feature.” Finally twenty-five Igorrotes arrived in early September to take up residence in a hastily constructed “village."

And what did fairgoers learn about these people of the new Pacific America? One reporter placed them firmly in an existing racial hierarchy by noting that they “look as intelligent as the average Indian.” Other newspaper and magazine stories emphasized their difference from Oregonians. They were pagans and barbarians who knew to “obey the white man implicitly” but they were childlike, and could “pout and act like unruly children” when the Americans in charge of their village gave them instructions that they did not like. They did not normally wear many clothes, although the women had to put up with an American blouse and skirt while they were in Portland. And, their diet in the Philippines sometimes included dogs, a fact that gave Oregonians endless amusement. “Dog-eaters here!” trumpeted the Oregonian. “If you have a valuable canine, particularly if he is fat, beware.” Before coming to Portland, said the Lewis and Clark Journal, they had exacted a promise that they could continue to indulge in feasts of roast dog and dog stew. “We saw the dog-eaters,” one Portlander recorded in her diary, “and had just lots of fun.” Unmentioned was the fact that Lewis, Clark, and their companions had also eaten dogs on their long trek.

Then as now, Oregonians could marvel at exotic people with darker skins—and carefully define them as inferior—because the state was very white and very northern European. Although the percent of foreign-born residents in the state’s population peaked between 1880 and 1910 at 16 to 18 percent, most of the immigrants were reasonable facsimiles of the folks who had been in charge since the 1840s. Finns and Swedes and Norwegians were helping to fill up the coast. Germans and Canadians helped to fill up the Willamette Valley. In contrast, the number of Chinese had been going down since immigration was restricted in 1882; most were living in Portland or in small eastern Oregon communities like John Day. And African Americans were counted in the hundreds, although out-of-towners were likely to encounter them as railroad porters, Pullman car attendants, or waiters in dining cars.

Oregon’s black population did not grow substantially until World War II, when shipyard jobs brought workers and families by the tens of thousands. Because few neighborhoods were open to black residents in 1941 or 1942, thousands of black families found housing in the huge wartime community of Vanport, built where Portland International Raceway and Heron Lakes golf course are now found. Many other black newcomers lived in temporary housing at the Guild’s Lake project on the old fair site. Both locations were comfortably isolated from white neighborhoods. In 1948, after a Columbia River flood destroyed Vanport, some refugees ended up in trailers at Guild’s Lake for as many as four years before they were removed for industrial expansion.

The state’s foreign-born population fell steadily from 1910 to a low of 3 percent in 1970. Since then, Oregon has slowly begun to look more like the state of the 1870s as the proportion of foreign born climbed back to 8.5 percent in 2000—half of whom had arrived in the U.S. since 1990. Twelve percent of Oregon families spoke a language other than English at home. The renewed immigration was the result of multiple factors: the general easing of restrictions on immigration to the U.S. with the Immigration Reform Act of 1965, the arrival of groups such as Ethiopians and Russians fleeing political turmoil or economic uncertainty, and the growing engagement of Oregon with the global economy.

Multicultural Oregon in 2010 was Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander (13,000), American Indian (53,000), African American (69,000), Asian American (141,000), and Hispanic (450,000). The Mexican American and other Latino population was the fastest growing group, bringing increasing diversity to Portland and its suburbs, to Marion, Polk, Jefferson, Morrow, Umatilla, and Malheur counties, to Hood River, The Dalles, Boardman, and Hermiston. Indeed, Hood River County had the highest proportion of foreign born among Oregon counties. Oregonians of Asian ancestry were divided among different national groups. Asian Indians, Chinese, Filipinos, Japanese, Koreans, and Vietnamese each accounted for between 12,000 and 30,000 residents. Many, but not all, lived in the Portland area, with identifiable concentrations of Koreans in Beaverton, Vietnamese in east Portland, and Asian Indians in Washington County.

© Carl Abbott, 2004. Updated and revised by OHP staff, 2014.

Sections

Related Historical Records

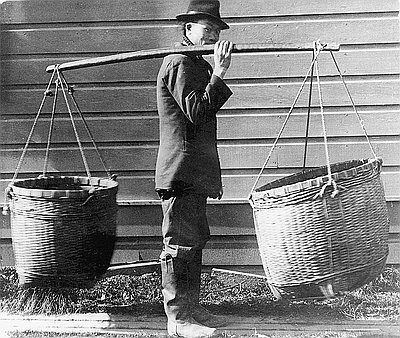

Chinese Street Vendor

This vendor is probably selling vegetables. Chinese gardeners supplied a large proportion of Portland's residents with fresh vegetables. The vendors carried produce through the streets in large baskets …

The Igorrote [sic] Tribe from the Philippines

This article was published in the Lewis and Clark Journal in October 1905. It discusses the exhibition of Igorot people at the Lewis and Clark Centennial Exposition and …

Second Oregon Crosses River in Philippines, 1899

This photograph shows Company I of the Second Oregon Volunteer Infantry Regiment crossing a river (identified as either the Quinqua or the Norzagaray) in the Philippines during the …