Outposts, Farms, and Missions

The commerce-oriented exploration of the North Pacific Coast by European and American sea captains became active during the 1790s. The 1792 incursions into the mouth of the Columbia River and upstream by American trader Capt. Robert Gray, soon followed by a party from the English expedition of Capt. George Vancouver, mark the beginning of many changes to Oregon’s built environment. Driven first by the commercial value of the sea-otter fur, European and American traders soon found other opportunities in another pelt, that of beavers. During the early 1800s, a network of mercantile posts spread over North America from eastern Canada, most famously those of the British-backed Hudson’s Bay Company, moving toward the Oregon Country. American fur interests also began to work westward from St. Louis into present-day Wyoming and the Dakotas.

American army captains Meriwether Lewis and William Clark and their Corps of Discovery arrived in the late autumn of 1805 at the mouth of the Columbia River, where they hoped to rendezvous with an American vessel that was sent to replenish their depleted supplies of food and trade goods. The explorers and their party had crossed the Rocky Mountains and followed the Columbia downstream to the Pacific, encountering lands and peoples not previously known to the American public. When they reached the Pacific shore, however, they were in an area where European and American traders had interacted with Native people for more than a decade. Those traders, had come and traded but had left no settlement behind.

The Corps of Discovery faced a long wait on a storm-lashed coast that winter, and they needed shelter. They built Fort Clatsop for their winter quarters, naming it for the local Chinookan band. Fort Clatsop was constructed of logs that were saddle-notched and stacked horizontally, two rectangular structures facing across a small courtyard. The fort was enclosed with a vertical log palisade with gates. The chimneys were made of wood twigs plastered with mud to prevent them from burning. While Douglas fir, Sitka spruce, and western hemlock were trees that were unfamiliar to Lewis and Clark, the techniques and materials the Corps used to build Fort Clatsop were common in Appalachia and in the middle Mississippi River Valley, the homelands of most of the members of the Lewis and Clark expedition.

Only a few years after Fort Clatsop was abandoned in 1806, the expansion of the fur-trading industry brought sojourning trappers and traders into the Oregon Country from eastern Canada and the United States. Trading posts such as Fort Astoria (1811) of the American Fur Company and the Hudson’s Bay Company’s (HBC) Fort Nez Perce (1818) (in present-day Washington) were built as semi-permanent quarters for commerce and residence. Fort Vancouver, established in 1825 on the north side of the Columbia River by the HBC as its regional headquarters (factory), became the nucleus of a larger permanent settlement.

From the beginning, the business dealings at Fort Vancouver brought into the Oregon Country a diverse populace that reflected the territorial reaches of HBC, from London and eastern Canada to the mid-Pacific Ocean. At Fort Vancouver, Scots and French Canadians, Iroquois Indians, and Kanakas from Hawai’i mingled with local Kalapuyans and Wascos. Most of the buildings constructed at the palisaded fort reflected European-derived techniques, including those at the village where lower-level HBC employees lived, generally known as Kanaka Village.

The builders of many of the early Oregon Country fur-trading posts, of both British and American origin, were often voyageurs of French Canadian background. One of the common construction methods was known as poteaux sur sole or post-in-sill. A heavy timber frame was erected and held together with wooden pegs, and the space between—the walls—was filled in with horizontally laid logs or planks. The ends of the logs or planks were notched to fit into grooves in the frame and were then held in place with more wooden pegs. Such basic methods and materials were used to build houses, fur warehouses, trading rooms, granaries, blacksmith shops—the built components of a trading post. At Fort Vancouver, notched and stacked logs and hand-hewn timbers were used to build the initial buildings, while later structures used more sawn lumber after the HBC established a rudimentary water-powered sawmill in 1827.

By 1840, Euro-American traders and trappers were common in the Oregon Country. The structures they erected to carry on their enterprise necessarily used wood, that abundant and versatile natural building material, just as Oregon Indians had. While the newcomers easily adopted local materials, for the most part they neither adapted nor adopted the local Indian building techniques.

The traders and trappers from eastern Canada and the United States who came to the Oregon Country in the 1820s and 1830s were initially transients in a foreign land. The diminishing of the fur trade from over-exploitation during the 1830s coincided with the decimation of Native peoples in the lower Columbia River region, the result of diseases such as smallpox and malaria brought in by Euro-Americans. These circumstances encouraged some former fur-trade men to remain in the area and to engage in farming. A number of French Canadian voyageurs and American trappers retired from the fur trade and settled in the fertile Willamette Valley, where the Kalapuyans had created and maintained through annual burning a pattern of scattered open prairies for food and forage. Euro-American settlers viewed these prairies as unutilized and available land that would require little work to be readied for growing wheat and other crops. Even though the Oregon Country was, by this time, disputed territory among Indian, British, and American interests, these settlers asserted their permanent residence by constructing substantial houses and farm buildings and by marrying Indian women and raising families.

Widely scattered at first, these settlers farmed along the banks of the Willamette River and its tributaries, especially the Yamhill and the Tualatin rivers, near such places as French Prairie and Elliott Prairie, the Chehalem Hills, the Pudding River (Rivière au Boudin), and Mission Bottom. The first farm houses were simple log or hand-hewn timber structures, assembled using the typically French Canadian post-in-sill method or built of hewn logs in a fashion that was traditional in the American settlements of Appalachia and the Ohio River Valley. The settlers also constructed sheds and barns for livestock and storage and granaries to store grain. These, too, were first built of logs and hewn timbers.

The 1830s brought another early group of sojourners who soon became permanent settlers—the missionaries, both Protestant and Catholic. The earliest Protestant missionaries, such as the Rev. Jason Lee, initially came to evangelize among the Indians, a calling that required them to build school and church buildings as well as residences and farms. Roman Catholic missionaries came first from Quebec, responding to requests from the French Canadian settlers for priests to come and settle among them. Both groups brought with them vernacular building traditions and practices that soon adapted to Oregon materials.

© Richard H. Engeman, 2005. Updated by OHP staff, 2014.

Sections

Native Ways and Explorers' Views before 1800

Euro-American Adaptation and Importation

Sawn Lumber and Greek Temples, 1850-1870

Architectural Fashions and Industrial Pragmatism, 1865-1900

Revival Styles and Highway Alignment, 1890-1940

International, Northwest, and Cryptic Styles

Glossary

Built Environment Bibliography

Related Historical Records

Hudson's Bay Company Blanket

White blankets like this Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC) blanket were among the first to be traded among fur trappers and Native Americans in North America. They were especially …

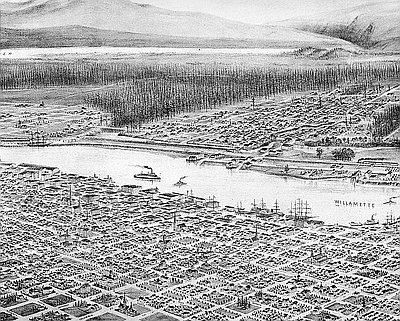

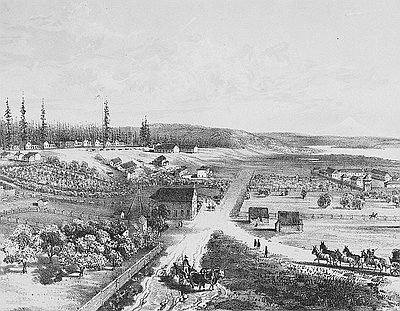

Lithograph of Fort Vancouver

This 1854 lithograph of Fort Vancouver was originally drawn by Gustavus Sohon while he and the U.S. Pacific Railroad Expedition and Survey team conducted a survey for railroad …

Robert Gray's Sea Chest

This chest is believed to have accompanied Captain Robert Gray on the second voyage of the Columbia Rediviva to the Northwest Coast, during which Gray made the first …