Dams and the Onset of the Modern Age

If there is a significant moment that marks the onset of the modern age, it may be August 6, 1945, the day an American B-29, the Enola Gay, dropped a five-ton uranium bomb known as “Little Boy” on the Japanese port city of Hiroshima. The United States government’s report of the event that day ended with this terse statement: “It is a harnessing of the basic powers of the universe.” The Medford Mail-Tribune editorialized that it was “a date for school boys to remember, as marking the end of one great epoch and the start of another.”

Because of Oregon’s proximity to the Pacific theater of military operations, Japan’s surrender on August 14, 1945, held special meaning for Oregonians. A day later, the Coos Bay Times reported that local communities were calm “like a ship at sea after the storm.” Farther north, along the coast, the Astorian Evening-Budget observed that business and industry stood still as people recovered from the previous day’s revelry. In the far northeastern corner of the state, the East Oregonian declared: “the war is over and a new era is at hand.” A few days after the battleship U.S.S. Missouri sailed into Tokyo Bay to formalize the surrender on September 2, the Medford Mail-Tribune praised the American free-enterprise system for its ability to produce “in conflict as well as tranquility” and for its contributions to winning “the greatest war in history.”

There was widespread belief across the United States that wartime scientific advances, including the atomic bomb, would redound to human benefit. The Hanford Evergreen Works on the Columbia River, near Richmond, Washington, had been a Manhattan Project site during the war. It promised a future for Oregon and the Northwest with inexpensive and clean electrical energy. Wonder chemicals such as 2-4D and DDT—“the atomic bomb of insecticides”—were evidence to Americans that the future would also be free of destructive and annoying pests and weeds. In addition, there was the promise of a push-button paradise—LP records, Polaroid cameras, automatic transmissions, electric clothes dryers and refrigerators, automatic garbage disposals, and vacuum cleaners.

Writing for New York Times Magazine in late 1945, Oregon’s popular and influential journalist, Richard Neuberger referred to the Northwest as “The Land of New Horizons,” a place where people were “buoyant and cheerful.” The writer—and future U.S. senator—praised the region for its “treasure-trove of hydroelectricity,” its expanding acres of irrigated land, and its scenic majesty. With care and good stewardship practices in its fields and forests, Neuberger believed, the Northwest had a promising future.

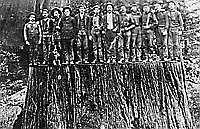

To anticipate and plan for that future, the Oregon legislature created the Postwar Readjustment and Development Committee, which issued monthly reports for five years. From today’s vantage, the bulletins read like a prescription for the massive reordering of the Oregon landscape: building dams on the Columbia, Snake, and Willamette Rivers; developing the irrigation potential of the middle Deschutes, the Klamath Basin, and the Ontario and Umatilla districts in eastern Oregon; expanding the state’s highways; “straightening” rivers; building jetties and deepening harbors; and funding agricultural and forestry research. The committee occasionally addressed looming problems, such as deforestation, water pollution, and declining salmon runs. In a scathing report in early 1946, it referred to the condition of the Willamette River as “a State shame.”

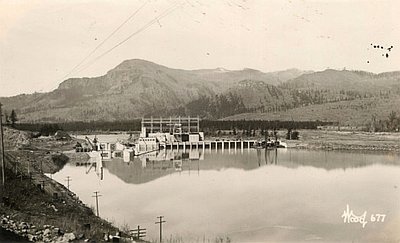

The most ambitious postwar development plans for the Pacific Northwest centered on the region’s waterways, especially the Columbia and its major tributaries, the Snake and the Willamette. Chambers of commerce and development groups in Oregon aggressively lobbied Oregon’s congressional delegation to promote projects on the Columbia and the Willamette.

Tribes, sports and commercial fishers, conservation groups, and those who wanted to protect scenic waterways fought tenaciously against the dam proposals. At least through 1947, it was not certain that the river developers would prevail. There were other alternatives, and opponents raised stiff opposition to the proposed McNary, The Dalles, and lower Snake River dams and the multipurpose Willamette Valley Project.

Dam-building opponents forced a series of public hearings that placed the outcome of some of the Columbia River and Willamette projects in doubt. Columbia Basin development reached a critical juncture in the fall of 1946 when the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service suggested a ten-year moratorium against building more dams on the Columbia and lower Snake Rivers.

In June 1947, at the most notable of the “fish versus dams” hearings in Walla Walla, Washington, the Columbia Basin Interagency Committee (CBIAC) took two days of testimony. Perhaps the most compelling dissent came from Indian opponents to dam-building, who warned that the dams would severely threaten fish and damage tribal cultures. After sifting through thousands of pages of testimony, CBIAC advised against the moratorium and passed that recommendation on to its parent committee in the nation's capital. The Federal Interagency River Basins Committee voted unanimously against the moratorium. The great Columbia River flood in the spring of 1948 and the destruction of the wartime housing project at Vanport marked the coup de grace for river development opponents.

In the years immediately following the war, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers designed and directed the construction of the Willamette River’s multi-purpose dam system. Fishery interests who opposed the Willamette Valley Project directed much of their criticism at the proposed dams that would block the upstream movement of migrating salmon. The construction of Detroit and Lookout Point dams suggests that most of those objections fell on deaf ears.

The Corps did modify its plans for a huge dam that would have flooded much of the McKenzie River Valley and instead built dams on two tributary streams, the Blue River and Cougar Creek. Opposition from fishery interests, especially those who cited the McKenzie River as a world-famous trout stream, played a significant part in persuading the agency to modify its original proposal.

© William G. Robbins, 2002. Updated and revised by OE Staff, 2014.