New Assaults on Indian Land

During this period, Native people continued to suffer a declining population and a diminishing land base, and they were denied access to important traditional gathering, hunting, and fishing grounds. They faced often harsh and inhumane federal and state policies. Some Paiute bands, for example, who had joined the Bannocks in their skirmishes with the U.S. Army in eastern Oregon and south-central Idaho in 1878, were moved far from their homelands to the Yakama Reservation in central Washington. Despite prohibitions against leaving reservations, many people sought seasonal work in eastern Oregon’s wheatfields, the orchards of the Yakima and Hood river valleys, and the Willamette Valley’s hopyards and berry fields. Many men participated in year-round timber harvesting. Through such means, reservation people achieved a degree of autonomy and contributed to Oregon’s agricultural economy.

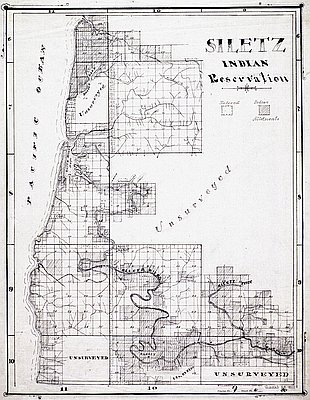

The U.S. government had begun carving huge slices of land from the coastal reservation in 1865, when it opened the land between the Yaquina and Alsea watersheds to white settlement. Ten years later, two additional areas were opened to homesteaders, from Cape Lookout south to the Salmon River and from the Alsea River south to the Umpqua drainage. Congress added to the assaults on Native land when it passed the General Allotment Act in 1887—also known as the Dawes Act—a measure ostensibly designed to encourage Indian farming. The act divided tribal lands into allotments for individuals in an attempt to destroy tribes by separating their communal lands. The new policy promoted the idea that the true route to civilization involved an incentive to work that was possible only through the individual ownership of property.

The Dawes Act was a direct attack on Native people, and reservations were reduced by approximately 90 million acres before the act was rescinded in 1934. The Siletz and Grand Ronde reservations suffered the most, as large acreages of valuable timberland were transferred to non-Indian owners. The Siletz people were forced to give up 192,000 acres for seventy-four cents an acre after the Secretary of the Interior declared that unallotted lands on the reservation were surplus. The Cayuse, Umatilla, and Walla Walla lost most of their aboriginal land base, an estimated 87,000 acres, as a result of the act.Allotment sharply diminished the size of the Umatilla Reservation, with many individual tracts winding up in non-Indian hands. The Burns Paiute in Harney County received 160 acres per head of household, but the sagebrush-covered land they were given lacked water for irrigation and proved nonarable. Beginning in 1892, some members of the Coos, Lower Umpqua, and Siuslaw tribes obtained allotments, but many lands were blocked by officials of the Siuslaw National Forest, who claimed the land was unsuitable for farming.

There were other aggressions against Indian nations in Oregon during the later part of the nineteenth century. President Ulysses S. Grant’s Peace Policy, for example, originated in the early 1870s when the government turned over the control of reservations to Christian organizations. The purpose was to procure “competent, upright, faithful, moral, and religious agents, to distribute the goods and to aid in uplifting the Indians’ culture.” Indian policy had been rife with corruption, especially in the management of the Indian Service. The Grant Administration reasoned that turning to religious groups would remove the onus of impropriety.

The Indian Bureau, for example, granted the Methodist Episcopal Church control of the Siletz Reservation on the central coast. The five church-nominated agents who served at Siletz while the Peace Policy was in effect were less corrupt than their predecessors, according to historian E.A. Schwartz, but they were no more effective. The Methodists also warred among themselves over management of the reservation, targeting their first agent, Joel Palmer—the original architect of the coast reservation—for not proselytizing for the church. Palmer observed that “it is useless to preach Christian conversion to a starving man—first feed him.” He resigned rather than fight the Methodists.

The Indian Bureau used other efforts to advance assimilation among Oregon Indians, including operating off-reservation boarding schools. The objective was to establish schools hundreds of miles from reservations so that Indian children would be removed from their parents and tribal affiliations. Discipline at the boarding schools was severe and rigid. Children were ridiculed for speaking their home languages and for their beliefs, manners, dress, and long hair. Runaways were whipped, and parents were sometimes denied the right to visit their children. In some cases, students were not allowed to return home for vacations.

The first off-reservation boarding school in the American West was the Forest Grove Indian Industrial and Training School, established at Pacific University in 1880. The first students to enroll—from Washington Territory’s Puyallup Reservation—were put to work helping construct buildings for the institution. Despite efforts to increase numbers, including forcible recruitment, a high mortality rate among students and suspicious tribes limited enrollment. When the Forest Grove academy suffered a major fire during the winter of 1885, the Indian Bureau directed the building of a new school north of Salem. Officially designated the Salem Industrial Indian Training School, the school operates today as the Chemawa Indian School.

Chemawa functioned much like the Forest Grove facility, with students—including the first “carpenter boys”—performing most of the manual labor. As more students arrived, school officials sent them to work for local farmers, with their wages used to purchase additional land for the institute. When the facilities were fully operational in 1887, the school enrolled children from across the American West and Alaska. Some of the enrollees died at the school.

The policy of forced assimilation was a failure. The effort to break tribal attachments proved elusive; and despite the harsh environments, Chemawa and other boarding schools laid the groundwork for the pan-Indian movements of the twentieth century. By bringing together children of many tribes, boarding schools unintentionally promoted cultural diversity and helped Native American identities survive.

© William G. Robbins, 2002. Updated and revised by OE Staff, 2014.

Sections

Related Historical Records

Picking Cranberries at Sandlake

This photograph shows workers, primarily women and children, harvesting cranberries near Sandlake in Tillamook County. It was taken around 1912. Massachusetts-native Charles D. McFarlin is generally credited with …

Siletz Indian Reservation, 1900

This map, produced by the Willamette Pulp and Paper Company, shows what remained of the Siletz Reservation in 1900. Each of the small squares on the map represents …

River Indians and Reservation Indians

This excerpt from an 1874 report by N.A. Cornoyer, agent for the Umatilla Indian Reservation, describes the development of a new geography of Native identity in the latter …