Japanese Forced Removal and Incarceration

Although many have described United States’ involvement in World War II as the “good war,” the conflict also produced one of the most notable violations of civil rights in American history. The removal of 120,000 Japanese Americans from the Pacific Coast and their incarceration in the interior West, historian Roger Daniels writes, brought about “one of the grossest violations of the constitutional rights of American citizens in our history.” The United States and the Canadian province of British Columbia evacuated all persons of Japanese descent from the Pacific Coast within three months after the bombing of Pearl Harbor in December 1941. The relocation remains the central historical reference point for modern Japanese-American history.

Although military references appear in all the justifications for relocation, the directive was political. When President Franklin Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066 on February 19, 1942, he set in motion policies that permitted the forced evacuation of Japanese American citizens and resident aliens to inland concentration camps. Beginning in early March, Gen. John L. Dewitt of the Wartime Civil Control Administration directed the relocation process beginning. He ordered Japanese in restricted zones along the Pacific Coast to report to temporary assembly points to await transfer to the camps in the interior. Nearly two-thirds of the Japanese imprisoned were American-born citizens, even though several highly placed military figures assured civilian authorities that Japanese Americans posed no threat to the internal security of the United States.

The order for Oregon’s Japanese to assemble at Portland’s Pacific International Livestock Exposition Center in March 1942 gave families only a brief period to gather personal belongings and leave their homes. The assembly center, which is now home to the Multnomah County Fair, housed approximately 4,500 Japanese during the spring and summer of 1942. Families lived in whitewashed, 200-square-foot livestock stalls, with straw mattresses, a single lightbulb, and uninsulated wooden walls and floors. Open cafeterias and communal showers compounded the lack of comfort and privacy. George Azumano, a Portland native, remembered that the stench of animal dung was still in the air.

The War Relocation Authority (WRA) and its director Dillon Myer eventually operated ten camps, all of which were surrounded by barbed wire and guarded by U.S. Army troops. Tule Lake in California, Heart Mountain in Wyoming, and Minidoka on the sweeping Snake River plain in Idaho housed most of the Japanese Americans from the Pacific Northwest. Although some prisoners could attend college or work as farm laborers in the interior West, most remained in the camps until the war in the Pacific began to wind down in late 1944. Three challenges to the evacuation command went to the Supreme Court, arguing against the incarceration of American-born citizens. In each instance, the Court upheld the federal order.

Even before the government issued the relocation order, it had restricted the movement of all people of Japanese descent. The City of Portland prohibited Japanese from being outside their homes between six o’clock in the evening and eight o’clock in the morning, and they could not travel more than a few miles from their residences. One of those who deliberately challenged the curfew was Hood River’s Minoru Yasui, an attorney and reserve army officer. Yasui was convicted of breaking the curfew in federal district court, and his appeals eventually gave way to other cases, especially that of Gordon Hirabayashi, who challenged the constitutionality of the evacuation order.

When the war ended, the U.S. government sent about eight thousand Japanese Americans to Japan. Known as “renunciants,” these people reputedly had renounced their citizenship during their stay in the camps. In many instances, the “renunciants” were under tremendous pressure in the relocation centers and were reduced to pleading for favors. In exchange, some of them renounced their citizenship or signed away the citizenship rights of their children. The Department of State and the Department of Justice fought the efforts of the “renunciants” to regain their citizenship rights from 1944 until 1959, when the federal government ceased to oppose such requests.

When the federal government permitted the prisoners to return home in December 1944, most of them remained in the camps for another year because of the anti-Japanese sentiment in their hometowns. A few regional politicians, including Washington Senator Warren Magnuson and Oregon Congressman Walter Pierce, called for tough restrictions against Japanese Americans when they began to returns. In Hood River, shopkeepers posted signs announcing “No Jap Trade Wanted,” a prejudice that made it necessary for returning farmer Ray Yasui to travel twenty-five miles to The Dalles to purchase supplies. Hood River newspapers also published a petition signed by many local residents declaring that the Japanese should not return to the valley. In one of the most egregious incidents, the Hood River American Legion removed the names of sixteen Japanese American servicemen from the local honor role, creating a national furor. Still other Japanese Americans returned to hostile receptions and loss of property, especially former truck farmers in the Portland metropolitan area.

After the war, the Japanese American Citizens League (JACL) sought justice for those who had been imprisoned. One of the organization’s important achievements was passage of the Japanese American Claims Act in 1948, a measure designed to help the former prisoners recover lost property. The JACL argued that “principles of justice and responsible government require that there should be compensation for such losses.”

As it worked its way through Congress, the bill enjoyed broad support and received high praise from cabinet members and the former leadership of the WRA. The legislation provided only partial redress for wartime losses, but as historian Roger Daniels points out, it “was an important symbol of the improved image of the Japanese American people.” It was not until 1990 that Congress made reparations to those who had been in the camps, appropriating $17.2 million for Japanese American survivors and their dependents.

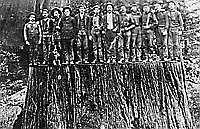

World War II had far-reaching effects on the region’s forest products trade and its dependent communities. After years of seasonal and market-induced unemployment, Northwest timber districts—especially those with large stands of old-growth timber—entered a period of sustained expansion that brought full employment and regular paydays. With self-sacrifice as their rallying cry, lumber trade officials informed the U.S. Forest Service that trees were less important than human lives and that the United States should forego “future needs for immediate demands.” Appeals to sustainable forestry practices and community stability, they argued, should be sacrificed for increased production.

During the peak of the wartime demand for lumber, the labor shortage was the only factor that limited the output of wood products. Forest Service Chief Lyle Watts, who had worked in Region Six (Pacific Northwest), noted in his 1944 annual report that national forests were supplying 10 percent of all timber harvested in the nation. If that trend continued in the heavily timbered sections of Oregon and Washington, Watts feared that it might lead regional foresters to “exceed sustained-yield cutting budgets.” He warned: “There must be no yielding to such pressures.”

The changes that took place during World War II would have lasting influences on northwestern forests. The shortage of workers placed a premium on labor-saving equipment such as chainsaws and other devices to speed production. The increasing use of diesel-powered yarding machines placed a priority on clearcutting practices, harvesting methods that became standard across the region’s timber districts after the war. New and more powerful technologies and the construction of miles of logging roads into western Oregon forests compounded erosion and landslide problems and accelerated the spread of a root fungus in southern Oregon’s Port Orford (white) cedar district.

© William G. Robbins, 2002. Updated and revised by OE Staff, 2014.

Sections

Related Historical Records

Japanese Evacuees, Portland Assembly Center

In May 1942, Portland-area Japanese and Japanese Americans—both Issei (first generation) and Nisei (second generation) —were evacuated to hastily constructed temporary living quarters in the Pacific International Livestock …

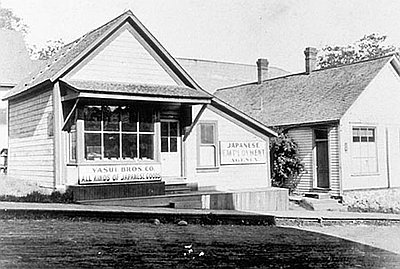

Minoru Yasui (1916-1986)

This photograph shows the Yasui Brothers Store at the corner of First and Oak Streets, Hood River, circa 1928. Masuo Yasui, Renichi Fujimoto (also known as Renichi Yasui), …

Japanese Evacuee Tops Sugar Beets

This 1943 Oregonian photograph shows a Japanese American “evacuee” topping sugar beets in Nyssa, a small town on the Idaho state line in Malheur County. On February 19, …