Treaties and Reservations

Once the federal government resolved the western Oregon Indian question to its satisfaction, officials turned their attention to central and eastern Oregon. Once again, federal officials moved to forcibly relocate Indians to reservations, where they would be removed from main travel routes. The stated objective was to free land for white settlement.

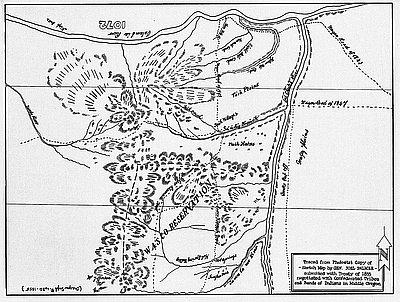

The Umatilla Reservation, established at the 1855 Walla Walla Treaty Council, was negotiated by Washington Territorial Governor Isaac Stevens and Oregon Superintendent of Indian Affairs Joel Palmer. The treaty ceded 6.4 million to the United States government and reserved to three tribes—the Cayuse, the Umatilla, and the Walla Walla—246,000 acres in southeastern Washington and northeastern Oregon. It also reserved for them the right to hunt and fish in their “usual and accustomed places.” Reservations for the Nez Perce and Yakama were also created at the Walla Walla Treaty Council.

That year, Palmer pursued a similar strategy on the mid Columbia River with the Warm Springs (the Tygh, the Tenino, the Wyam, and the John Day), the Wasco, and the Paiute to establish the Warm Springs Reservation. In return for 464,000 acres of reserved lands in north-central Oregon and the right to fish and hunt in their “usual and accustomed places,” the tribes ceded more than 10 million acres to the federal government.

The Coast Reservation was established by executive order in 1855 for people on the coast and in the Umpqua and Willamette valleys. Comprising nearly 125 miles along the Oregon Coast, from present-day Tillamook to Douglas County, the reservation had three administrative units: Grand Ronde Agency (northern), Siletz Agency (middle), and Alsea Subagency (southern). The U.S. government replaced the Coast Reservation with the Grande Ronde Reservation in 1857 and the Siletz Reservation in 1865.

The Confederated Tribes of Coos, Lower Umpqua, and Siuslaw Indians agreed to cede 1.9 million acres to the federal government in 1855 in exchange for a treaty that would compensate the tribes with food, employment, education, and health care. The treaty was never ratified, and the people were held against their will in an area on the lower Umpqua River. In 1859, they were marched by the Bureau of Indian Affairs to a reservation on the Yachats River, where many died of starvation, exposure, and disease. In 1876, the land along the Yachats was opened to settlement, and tribal members were released from the reservation, but they found their ancestral lands greatly changed./

© William G. Robbins, 2002. Updated and revised by OE Staff, 2014.

Sections

Related Historical Records

Wasco (Warm Springs) Reservation Map, 1855

From 1854 to 1855, Joel Palmer, the superintendent of Indian affairs for Oregon Territory, negotiated nine treaties between Pacific Northwest Indians and the U.S. government. Many Indians agreed to …

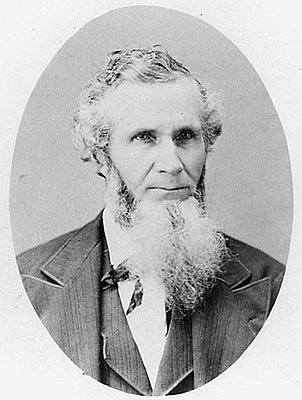

Joel Palmer (1810-1881)

On October 7, 1845, Joel Palmer made the first recorded climb on Mount Hood. He wore moccasins that exposed his feet to ice and carried little food. After …