The Literature of Oregon

The earliest published writing in the Pacific Northwest was the work of the fur men and explorers, including the journals and travel accounts of Alexander Ross, Ross Cox, Peter Skene Ogden, Osborn Russell, David Thompson, David Douglas, and Meriwether Lewis and William Clark. It was a literature that described the people and the landscape of Oregon and recorded information about the region’s climate, topography, and river systems—establishing the facts of place.

The journals, travel accounts, reconnaissance reports, and the later federal surveys gave the region and state an identity for the rest of the nation. Most of the literary efforts that followed—prose, poetry, memoir, fiction, and history—engaged larger interpretive themes that linked events and circumstances over time. When regional literature comes of age, literary historian Harold Simonson contends, “both artist and the region come alive through the transforming power of imagination and spirit. Person and place are wedded to each other.”

William Lysander Adams, a schoolteacher with an eccentric, sarcastic wit and a sharp pen, wrote Oregon’s first literary piece, A Memodrame Entitled “Treason, Stratagems, and Spoils” in Five Acts, under the pen name Breakspear. First published in the Oregonian in 1852, the play skewered Oregon’s Democratic Party, especially its public voice, the Statesman and its editor Asahel Bush. Adam’s play, historian Edwin Bingham writes, was “local literature with a vengeance.”

In 1854, Margaret Jewett Bailey’s, the first women writer to appear in print in Oregon, published Grains, or Passages in the Life of Ruth Rover, the region’s first novel.

A thinly disguised story based on the author’s marriage to William Bailey, a drunken missionary, Grains was shredded by the Oregon press, with most of the venom directed at the author because she was a woman and a divorcee.

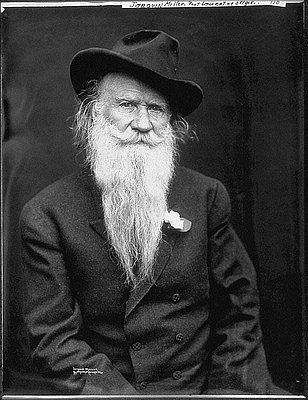

The first Oregon writer to emerge as a significant regional and national figure was Joaquin Miller (1837-1913), a colorful character who moved about Oregon through a series of careers as a schoolteacher, judge, and defender of the South during the Civil War. Miller eventually moved to Portland and then to California, where he made his reputation as the “Poet of the Sierras.” He never achieved the acclaim at home that he received in Europe, where he appeared dressed in buckskin and portrayed himself as the “Byron of the West.” Miller’s best known works are two histories, Unwritten History: Life Among the Modocs (1873) and An Illustrated History of Montana (1894), and a book of poetry, Songs of the Sierras (1875). Many critics have claimed that his estranged wife, Minnie Myrtle, was the better poet. An energetic woman with a flair for life, she published a contemptuous “defense” of her wanderlust former husband in the Oregonian (reprinted in the New Northwest).

More significant as a novelist and writer was Abigail Scott Duniway, an early suffragist and advocate for women’s rights and the author of Captain Gray’s Company: Or, Crossing the Plains and Living in Oregon (1859) and the best-selling Pathbreaking: An Autobiographical History of the Equal Suffrage Movement in the Pacific Coast States (1914). Another Oregon woman, Frances Fuller Victor, was a remarkably gifted writer and the author of several of the Hubert Howe Bancroft histories of the American West. The region’s first historian and an important national literary figure, Victor wrote River of the West (1871), a biography of fur-trapper Joe Meek based on oral interviews, and the two-volume History of Oregon for Bancroft’s multi-volume History of the Pacific States.

Among all of Oregon’s early literary figures, Charles Erskine Scott Wood (1852-1944) may be the most fascinating. Throughout his active life, he embraced several fields of activity—the military, law (with a degree from the Columbia University Law School), writing, painting, and humanitarian work. A graduate of the U.S. Military Academy at West Point, Wood saw service as a lieutenant in campaigns against northwestern tribes, and he accompanied Gen. Oliver O. Howard in the U.S. Army’s running battles with the Nez Perce in 1877. He recorded—and doctored—Chief Joseph’s famous surrender speech in the Bear Paw Mountains in Montana. In the Northwest, Wood was detailed to Camp Harney, where he fell in love with the Oregon desert, and he served a short stint as adjutant in charge of the officer academy at West Point. He was then was off to Portland, where he developed a highly successful law practice, representing railroad corporations and some of the city's wealthiest individuals.

Wood’s life was a paradox. He defended railroad monopolies by day and wrote radical essays for publications like The Masses after hours. The Oregonian once called him hypocritical for quietly accepting the largess of the railroads while espousing his anarchist views before the public. A man of immense personal charm and a gifted public speaker, he was a prolific writer, contributing a regular column to Pacific Monthly and writing short stories—under a pseudonym—for several magazines.

Wood was also a talented artist, exhibiting his work at the Portland Art Museum and other regional venues. Poet in the Desert (1915), published when he was sixty-three years old and influenced by his affection for eastern Oregon, is his best book of poetry. When he was seventy-five years old, he published Heavenly Discourse (1927), a series of dialogues between St. Peter and the Devil that brought him national and international acclaim.

Appealing to nostalgia and a romantic heritage, authors of historical fiction have enjoyed sizable audiences in the Northwest. The first Oregon writer of this genre to gain a popular readership was Eva Emery Dye, who was enamored with the “pioneer epoch” and who assured readers that her work was based on meticulous research in historical archives. In a series of fictional novels—McLoughlin of Old Oregon (1900), The Conquest (1902), and McDonald of Oregon (1907) —Dye wrote romanticized tales of Homeric figures struggling to create a civilization in the Northwest wilderness. Although the Oregonian and the Oregon Historical Quarterly praised her contributions, Frances Fuller Victor panned Dye’s work in the American Historical Review, criticizing the McLoughlin book for its literary weaknesses and for “the mingling of fiction with historical truth.”

If Dye authored romantic and frivolous novels, her contemporary John Reed was quite the opposite. Born to a wealthy Portland family, Reed was a radical journalist who published articles in The Masses and who was in Russia during the outbreak of the Bolshevik Revolution in the fall of 1917. He subsequently wrote the classic English-language account of the revolution, Ten Days That Shook the World (1919). After he was indicted under the Espionage Act soon after the book appeared, Reed left for Russia, where he died from typhus in 1920. Reed remains the only American buried at the Kremlin Wall Necropolis.

Reed’s wife, activist and journalist Louise Bryant, had come to Oregon as a young woman to attend the University of Oregon. She also wrote for The Masses and published Six Red Months in Russia: An Observer’s Account of Russia before and during the Proletarian Dictatorship in 1918. After Reed’s death, she continued to work as a journalist and published Mirrors of Moscow in 1923. As for Reed, he went without much honor in Oregon until 2001, when the Oregon Cultural Heritage Commission dedicated a bench for the homegrown radical in Portland’s Washington Park.

Two young, early twentieth-century Oregon writers, H.L. Davis and James Stevens, mark the transition in the literature of the Northwest. In an angry, privately published tract in 1927, Davis and Stevens accused regional writers of avoiding social realism, of penning nothing more than rubbish and “tripe.” Under the Latinate title, Status Rarum, the authors used wit and sarcasm to ridicule the region’s literary figures, including poetry and fiction writing classes taught at the University of Washington and the University of Oregon. They assailed a Salem literary monthly for “metrical ineptitude” and the “perverted taste” of an editor who published “the most colossal imbecility.” The authors went on to produce regional literary gems of their own, with Davis publishing Honey in the Horn in 1935 and Stevens Big Jim Turner in 1946.

With Honey in the Horn, which provided a sharp contract to the sentimental, melodramatic, and parochial novels of early regional writers, Davis became the only Oregonian to win the Pulitzer Prize for fiction. Adopting the initials “H.L.” after his reputed mentor H.L. Mencken, Davis was the first major Northwest novelist to have credentials to literary excellence. Honey in the Horn offered readers stark realism, with its protagonists—Clay and Luce—burping, picking their noses, and behaving in an unsavory manner. Early reviews panned the book for its vulgar and reprehensible language and its failure to portray the region in a more favorable light. Davis wrote four more novels, including Beulah Land (1949), and he also wrote poetry, including “Mid-September,” a moving and melodic commentary on the harvest season and the natural world.

Stewart Holbrook, a freelance writer in Portland, had many talents—logger, prizefighter, semi-pro baseball player, and watercolorist. Until his death in 1964, he was considered the dean of Northwest writers. Holbrook’s popular historical writings were uncritical, informal, often folksy, and filled with an ironic sense of humor. Among his best known works are Holy Old Mackinaw: A Natural History of the American Lumberjack (1938), Burning an Empire: The Story of American Forest Fires (1943), and The Columbia (1956). Under the name, “Mr. Otis,” Holbrook created artwork that one critic referred to as “wildly imaginative.”

The literary winds shifted again in the early 1960s with the emergence of Don Berry (1931-2001) and Ken Kesey (1935-2001), two gifted writers who gave a different style and tone to regional literature. Berry, who worked in the Reed College bookstore in Portland, published his best books, Trask, A Novel (1960) and Moontrap, A Novel (1962), within a two-year period. Based on careful historical research, the books confronted the issue of race in the fur-trapper culture of early Oregon. Berry spent his later years on Puget Sound’s Vashon Island, where he gained a reputation as a creative genius, writing music, poetry, and children’s literature and designing home computers. The Seattle Post-Intelligencer described Don Berry as the “Michelangelo of Puget Sound.”

Kesey gained preeminence with two best-selling novels, One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest (1962) and Sometimes a Great Notion (1964). A University of Oregon graduate, Kesey attended Stanford University’s creative writing program, where he studied with Wallace Stegner in a seminar that included Larry McMurtry and Wendell Berry. He volunteered to participate in U.S. Army-sponsored research involving LSD at the Stanford medical school and then joined a fun-loving, drug-culture group known as the Merry Pranksters. Celebrated in Tom Wolfe’s The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test (1968), Kesey and the Pranksters toured the country in a brightly colored school bus. Although he published other novels during the next three decades, none achieved the acclaim of his first two works.

The first Oregon poet to win the National Book Award was William Stafford. Educated in his native state at the University of Kansas, Stafford was a conscientious objector during World War II. He moved to Oregon in 1948 to teach writing at Lewis and Clark College in Portland. He received a Ph.D. from the University of Iowa in 1954 and was Oregon’s Poet Laureate from 1975 to 1989. Stafford wrote sixty-five books of poetry and prose, and his honors include service as a Consultant in Poetry—today’s National Poet Laureate—to the Library of Congress in 1970. With a reputation for gentleness and compassion, he was renowned for his talents both as a teacher and a writer.

Among Oregon’s contemporary writers, Ursula Le Guin is preeminent. The author of almost twenty novels, several collections of short stories and poetry, thirteen children's books, and collections of critical essays, she is a writer with catholic interests. The daughter of anthropologists Theodora and Alfred Kroeber, Le Guin won the Newbery Silver Medal Award for The Tombs of Atuan (1971) and the National Book Award for Children's Books for The Farthest Shore (1972), both in 1972. She also won the Lewis Carroll Shelf Award for A Wizard of Earthsea (1968) in 1979.

Raised in south-central Oregon’s sparsely populated Warner Valley, William Kittredge returned to his home ranch after a stint in college and the U.S. Air Force. After four short years in the valley as one of the bosses on the huge family spread, he left for the graduate writing program at the University of Iowa. From there, he moved west to join poet Richard Hugo at the University of Montana, where served as director of the creative writing program.

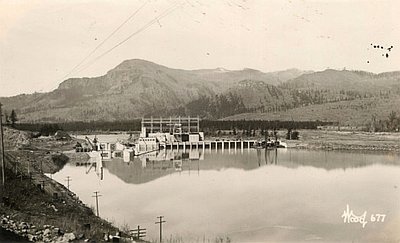

Kittredge’s books—especially his collection of personal essays, Owning It All (1987), and an autobiographical work, Hole in the Sky (1992)—are thoughtful reflections about the ways of inhabiting and living in the West. Balancing Water: Restoring the Klamath Basin (2000) is a beautifully illustrated and passionately written account of the history of water in the Klamath Basin.

Both in 1945 in The Dalles, on the Columbia River, Craig Lesley was educated at Whitman College, the University of Kansas, and the University of Massachusetts. His first two novels, Winterkill (1984) and River Song (1989), deal with several generations of Nez Perce who work in rodeo towns and on the Columbia River’s Native fishery and who seek to understand and retain their heritage. The Pacific Northwest Booksellers’ Association gave Winterkill and Sky Fisherman (1996) its Best Novel of the Year award. In 1992, Lesley received a PNBA award for his edited collection, Talking Leaves: Contemporary Native American Short Stories. Sky Fisherman was nominated for a Pulitzer Prize, and Storm Riders (2000) won the Oregon Book Award in 2000.

© William G. Robbins, 2002. Updated and revised by OE Staff, 2014.

Sections

Related Historical Records

Negotiating the Surrender

This sketch by Guy Howard depicts a scene from the surrender of Nez Perce Indians (Nimi’ipuu) to the U.S. Army in early October 1877. Guy Howard was the …

Abigail Scott Duniway votes

Abigail Scott Duniway, sister of Daily Oregonian editor Harvey Scott, was a novelist, newspaper publisher, teacher, pioneer, milliner, and suffragist. An overland pioneer of 1852, Duniway wrote a novel, one of …

Joaquin Miller, Poet Laureate of Oregon

Joaquin Miller was an Oregon writer and poet who first found fame in Britain by portraying himself as a flamboyant western frontiersman, telling colorfully exaggerated stories, wearing buckskin …