The Astorians and the Hudson’s Bay Company

The Astorians were the first fur traders to arrive. New York entrepreneur John Jacob Astor sent two groups of clerks to the Columbia River country—one by sea and the other by land. Arriving at the mouth of the Columbia in 1811 aboard the New York-based vessel Beaver, company clerk Ross Cox described the magnificent “productions of the country, amongst the most wonderful of which are the fur trees.” Traveling upriver and into the Willamette Valley, he described in his journal “a rich and luxuriant soil, which yields an abundance of fruits and roots.” Clerk Alexander Ross thought the Willamette country held excellent potential for agriculture, with an ideal climate that would “ripen every kind of grain in a short time.” And then there were the great runs of salmon in the Columbia River, a potential bonanza “were a foreign market to present itself.”

The Americans were not alone in attempting to secure a foothold in the Northwest. The Montreal-based North West Company sent Alexander MacKenzie, Simon Fraser, and David Thompson to traverse and map much of the Columbia Basin. Through them, the world learned about the region’s major mountain ranges and waterways. The Nor’westers established several fur-trading outposts at strategic travel corridors in the interior country, such as Fort Covile on the Columbia River in Washington. When the company received word about Astor’s project, surveyor and cartographer David Thompson was sent to give the North West Company a presence on the lower river. He ascended the Columbia River with seven men “to explore this river in order to open out a passage for the interior trade with the Pacific Ocean.”

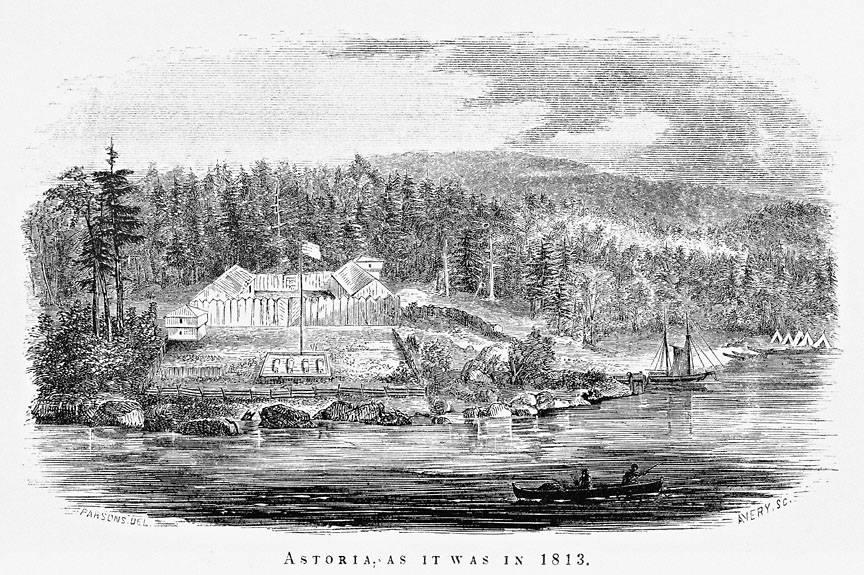

Thompson’s arrival at Fort Astoria worried Astor’s Pacific Fur Company clerks who were equally ambitious to move upriver in search of furs. With the outbreak of the War of 1812 and the expected arrival of a British sloop of war, Astor officials agreed to abandon the fort to the North West Company. Astorian Gabriel Franchère recorded that on December 12, 1813, William Black, captain of the British warship HMS Raccoon, claimed Fort Astoria for Great Britain and renamed it Fort George. Although the North West Company enjoyed a brief period in which it dominated the fur trade on the Columbia, it too fell victim to outside pressures in 1821, when the British government ordered the company to merge with its larger and more powerful competitor, the Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC).

Established in 1670, HBC controlled the fur trade in the region ion the late eighteenth century, taking over the old posts of the Pacific Fur and North West Companies. Upon merging with the North West Company, HBC immediately set about reorganizing its fur-trading activities under the administration of George Simpson, the new governor of the Northern Department, headquartered at York Factory in Manitoba, Canada. After a tour of inspection from the Canadian interior to the lower Columbia River in 1824, Simpson ordered that a major trading center by built on the north shore of the Columbia near the mouth of the Willamette River. Situated a hundred miles upriver from Fort George, Fort Vancouver became a focal point for trade and commerce, a place where local people negotiated agreements and, ultimately, where they would be exposed to disease.

Fort Vancouver consisted of thirty to forty houses, a hospital, storehouses for grains and trading goods, a sawmill, and workshops for carpentry, blacksmithing, and other activities. Nearby, HBC operated a shipyard, gristmill, dairy, farm, and orchard. The populations within and around the fort included French Canadians, Métis, Iroquois, Delaware, Hawai’ians, Europeans, and people from Native groups in Oregon. Cayuse, Umatilla, Walla Walla, and Nez Perce regularly brought furs and horses to trade with HBC, but the company controlled the landscape and rules of engagement with the traders.

Under Simpson, HBC pursued a strategy of trapping out areas south and east of the Columbia River. To slow the advance of American trappers and settlers into the region, Simpson ordered personnel to trap out the Snake River country in southeast Oregon. His fur-desert policy depleted the region of fur-bearing animals and left few attractions to trappers from east of the Rocky Mountains.

With John McLoughlin/ as chief factor, Fort Vancouver (1825-1846) was one of imperial England’s most distant outposts and arguably the most important settlement in the Pacific Northwest. Serving as the headquarters for HBC activities west of the Rocky Mountains, it linked the Oregon Country to international trade by exporting lumber, fur, salted salmon, beef, and grain. Under McLoughlin’s direction, it became an international port of call for visitors, including natural scientists, missionaries, and an occasional American empire builder.

In the Oregon Country, Fort Vancouver was the central clearinghouse for business activities that treated animals and other resources as commodities, as items that could be trade for profit. As an expression of Great Britain’s expanding commercial and imperial power, the Fort Vancouver post was a middle ground between Native and Western worlds, a place where people could mediate the terms and volume of trade. Until the 1840s, when white immigrants traveling west on the Oregon Trail began to populate the lower Columbia and Willamette valleys, Fort Vancouver was a colonial outpost among Native communities. The relationship between Native and white populations was rapidly reversing itself, however, as diseases were dramatically reducing the Native population. The loss of Native population coupled with the rise of white settlers immigrating to the Oregon Country resulted in a white majority in the region by 1845.

© William G. Robbins, 2002. Updated and revised by OE Staff, 2014.

Sections

Related Historical Records

Hudson's Bay Company Blanket

White blankets like this Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC) blanket were among the first to be traded among fur trappers and Native Americans in North America. They were especially …

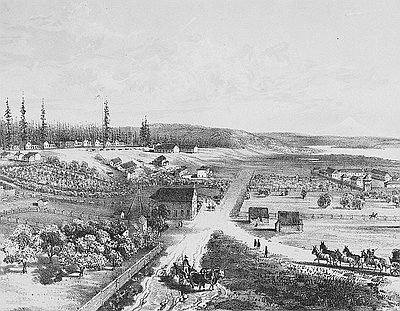

Lithograph of Fort Vancouver

This 1854 lithograph of Fort Vancouver was originally drawn by Gustavus Sohon while he and the U.S. Pacific Railroad Expedition and Survey team conducted a survey for railroad …

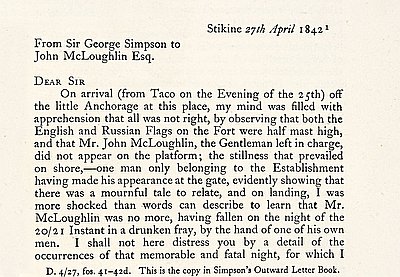

George Simpson to John McLoughlin, 1842

Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC) Governor George Simpson wrote this short letter to John McLoughlin, chief factor of the company’s Columbia Department, on April 27, 1842, to inform him of …